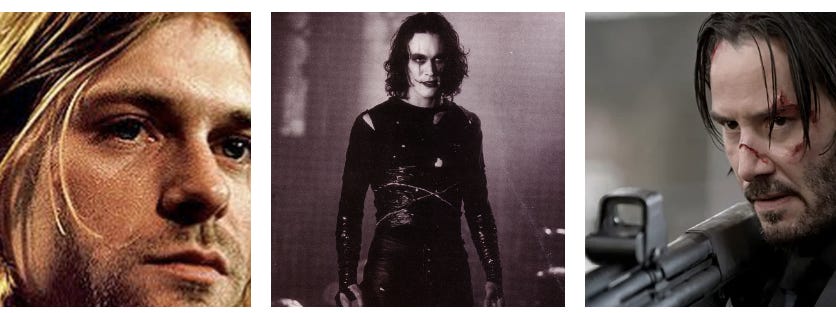

The Weight of Feeling: How ‘The Crow’ and ‘John Wick’ Embody Kurt Cobain's Grunge Image

Core tenets of grunge — bleeding-heartedness and thrashing against an unresponsive world — are best embodied within these two films that have a traditionally masculine aura about them.

Editor Note: this a banger

In the 2015 documentary Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, Cobain’s mother says of the musician that, as an infant, he felt deep, deep empathy. “He was so kind, and so worried about people, if they were okay, or if somebody got hurt,” says Wendy Cobain. Cobain was prescribed something approximate to ritalin very early on as a child, she goes on to add. In his suicide note, Cobain wrote:

I’m too sensitive. I need to be slightly numb in order to regain the enthusiasms I once had as a child. On our last 3 tours, I’ve had a much better appreciation for all the people I’ve known personally, and as fans of our music, but I still can’t get over the frustration, the guilt and empathy I have for everyone. There’s good in all of us and I think I simply love people too much, so much that it makes me feel too fucking sad.

Cobain touches upon something I’ve often felt and seen enacted in film, but never so succinctly communicated: empathy that feels like cold air on an exposed nerve, on a sensitive tooth, is weighty, can make it tough to function in the world. A mind mired in one’s own and others’ feelings, in memory, in loss — past, present, and apprehensions about future feelings — is often stuck in an obsessive cycle where the person fretfully tries to achieve either solace within the miasma of feeling or stable control, leaving the body to fall out of step with mundane reality. It’s not so much navel gazing as it is a listening to and honoring of, and potentially acting on one’s feelings, for better or for worse. Here, acting on one’s feelings means action directed by the ache felt within the psyche, prompted by empathy, as opposed to rational, regimented, planned action required by capitalism.

This empathy, this effusion of feeling — anger, sadness, indignation — has love as its bedrock, and found its apotheosis in the ‘90s with Cobain’s iteration of grunge, that countercultural sub-genre defined in music by distorted sound and “heartfelt and anguished lyrics.” Arriving on the heels of the apex of gender stratification that 1980s manufactured, grunge, specifically Cobain’s image’s iteration, was deeply feminist, presenting an alternate version of masculinity, or an alternate way to be a man, that was fluid, almost elastic and receptive as it projected a kind of safe presence that wasn’t domineering, but was rather respectful of goodness and self-aware as it made its case against a bitter and exclusionary status quo. Cobain’s image was apparently about feeling all the feels so intensely and with an impossible-to-fight focus, that revolutionary action or solutions to societal ails were not so much forgotten as they were in abeyance. Accordingly, grunge was, in 1992, defined as being “about not making a statement.”

As Cobain felt the pain of his empathy, communicating and transmuting it through music, Cobain’s image, his embodiment of grunge as a public person, was also apparently deeply aching. He started a conversation with his presence, made room for others’ feelings, presenting a kind of masculinity that was uncaring of traditional gender boundaries, that wept as much as it transgressed with its presence. In her seminal essay “Kurt Cobain Pushed the Boundaries of Gender and Made Room for Us All,” Niko Stratis writes of Cobain’s anger and intense feeling:

[His was n]ot an anger misplaced, mind you, but an anger languishing in abstraction. I always felt that Cobain, like myself and indeed a lot of people, was vainly attempting to pinpoint the things within himself that felt out of step with the world around him. He wasn’t angry at a system or a woman who had wronged him. He was frustrated, seeking an unattainable sense of control over himself, his own pain, and his place in the world.

Stratis goes on to describe Cobain’s discomfort with and within himself, the “internal strife” that raged on within him so publicly, and within his own lyrics, and ultimately how the complex and textured feelings he either displayed on his person or through his music challenged and frustrated traditional notions of gender. Traditional, suffocating cultural notions of oughts, societal expectations for success that delimited a person, all dictated by capitalistic, patriarchal society, would have been the ultimate cause of Cobain’s pain. Most compellingly, Stratis writes of the way in which Cobain’s uniqueness could not find rest within the structure and strictures of the world about him, and so worked instead to stand its dusty notions on their head:

The most striking thing about Cobain, outside of the flannel-clad bluster and bravado of grunge, was how he pushed the boundaries of his gender. He would regularly appear onstage wearing a dress over his usual attire of jeans and multiple shirts. As time wore on between the massive success of Nevermind and follow-up album In Utero, he seemed to revel in being seen as anything but what was codified as your average cishet man.

With Cobain, we have a person not only rebuking traditional masculinity, including its hard lines, expectations of suppressed feeling, abuse, and the subjugation of women (in a diary entry depicted in Montage of Heck, Cobain writes one of his foundational rules: a woman ought never to be hurt, while playing a gig or otherwise). We also have the coalescence of a figure so essentially an embodiment of grunge, because of the ways in which he felt radically unabashedly, the ways in which he communicated his feelings through his bleeding words, wore his heart on his sleeve. He was everything a man according to traditional notions ought not to be.

Cobain’s almost humanistic focus on the self, the vanity that Stratis delineates, stokes anger and spurs flailing attempts at fighting an impossible and cold system, revealing along the way an inability or unwillingness to control or rein in his own feelings, his pain, which leaves him out of step with the world. All of this bleeding-heartedness and thrashing within an unresponsive and unchanging world, which reflect the core tenets of grunge, are best embodied within two films that have a traditionally masculine aura about them. The first is 1994’s The Crow, which was produced in the period and is a crystalline depiction of the Cobain grunge ethos, and the second is 2014’s John Wick, which revives this ethos. These are two films that are doing something delicately radical, in the way Cobain was, and I think their reevaluation with this in mind will reveal that they are just as revolutionary.

Both The Crow’s protagonist Eric Draven (Brandon Lee) and Keanu Reeves’ John Wick possess that almost Gothic, near traditionally feminine effusion of feeling, of love, that was apotheosized by grunge as presented by Cobain. Both The Crow and John Wick are films that aren't about a drive to fix the system, and neither presents the kind of traditional hero narratives carried by other superhero movies. These latter superhero narratives have their protagonists concerned with the greater good, a concern that is made possible because the heroes, for the most part, lack the kind of ache that is allowed, vainly, to resound. Instead, Eric Draven and John Wick are deeply self-oriented, possessing the kind of vanity that Stratis speaks of; theirs is "not an anger misplaced, mind you, but an anger languishing in abstraction.” An anger allowed to languish unchecked.

Cobain, in the passage from his suicide note quoted above, says that if only he could numb the ache within himself, he would be all the more able to focus on the outward world. But it’s impossible to turn off our feelings, and so one languishes with and within an intense subjectivity, within a stony world. Eric and John, too, are trapped within this kind of subjectivity, exhibiting the vain anger emanating from an unignorable pain. They are not superheroes, but rather two individuals who, by virtue of their feelings, buck traditional notions and behaviors associated with toxic masculinity. They are two characters who explosively display a Cobain-esque tender masculinity, acting to satisfy their own desires and pains; they don’t so much care to fix the system, as they do to alleviate their own pain, however futile this may be.

For all their apparent presentation of the strength associated with traditional masculinity (muscular built, wielding of “macho” instruments such as guns), I wonder if many take pause to consider the ways in which Lee’s Eric and Reeves’ John are so beautifully aching, sad, all in their feels, unabashedly moving their bodies with (and reveling in) the kind of fluidity that an average cishet man, constrained by the imposing and persuasive strictures of traditional masculinity, would be terrified of enacting. The two are ultimately “seeking an unattainable sense of control over [themselves], [their] own pain, and [their] place in the world,” as Stratis says of Cobain. In understanding these two films through this lens, we can see how pivotal and transgressive they are, crafting as they do sprawling and complex characters who create room for us all.

You’re just gonna have to forgive me for that

It’s often said of Alex Proyas’ The Crow that it’s a quintessentially ‘90s film. Indeed, it’s not surprising that The Crow has grunge sensibilities, produced as it was during the height of the movement. Everything from its dark, Gothic aesthetic — the Poe-esque corvid that roves and looms over a dark, crumbling city perennially and for no meaningful reason on fire — to its shoegaze and distorted rock-drenched soundtrack allow for it to easily hew, visually and sonically, to the sensibilities of the prevailing culture of the decade that produced it. And upon closer inspection, it becomes even more compellingly evident that this film is saturated through and through with a pure and heartbreaking grunge spirit, by virtue specifically of Lee’s spellbinding, Cobain-esque performance.

The film is based on a graphic novel of the same name from 1989 by James O’Barr, who played an integral role in the film’s production, so much so that he dedicated the comic’s 2010 special edition to Lee. Beginning work on The Crow in the early ‘80s, O’Barr wrote and illustrated the novel as a means by which to work through the death of his girlfriend, who was struck by a drunk driver as she made her way to pick him up. O’Barr held himself responsible for her death, much in the same way he felt intense guilt over Lee’s death on the set of the film that brought his grief to life. In the story, Eric’s fiancée is named Shelly, “after Mary Shelley, who wrote Frankenstein,” O’Barr writes in the introduction to the special edition. He picked the name “Eric” for the doomed figure at his story’s core, naming him after the Phantom in The Phantom of the Opera, “because ‘Shelly’s’ death had turned me into a monster under my own skin, hidden by a stoic face of normalcy,” O’Barr writes.

Proyas’ film and Lee’s performance in it do a remarkable justice to O’Barr’s dark and tormented vision, giving the comic’s early-’80s Goth-rock leanings a contemporary and complementary grunge grit. Lee plays Eric, who, alongside his fiancée Shelly (Sofia Shinas), are murdered on Devil’s Night, the eve of Halloween dedicated to setting the city ablaze, by a group of thugs (T-Bird [David Patrick Kelly] and his gang, under the direction of Top Dollar [Michael Wincott]). Shelly is brutally raped before her murder by each of the gangmembers. Exactly a year after this fatal incident, Eric, whose soul spent the interim period in restless anguish and guilt over not having been able to save the singular love of his life, is resurrected for a single night by the mystical Crow. The film follows Eric as he, with the Crow as an aid and conduit for his supernatural powers, and dressed as a macabre anti-joker, avenges his and Shelly’s deaths, killing all of T-Bird’s gang so as to find a semblance of peace for his soul.

O’Barr and the film make a protagonist of the auxiliary trope of The Fool, or joker, presenting a kind of damned and depressed Don Quixote. Defined as a character who “has no idea what they’re doing,” The Fool, with a vague grasp of his enemies and friends, stumbles blissfully through the plot as a comic relief, protected only by their cheerful disposition, possessing as they do the blessing of Lady Luck. In medieval plays, The Fool would be a stand-in for the audience, or the average civilian; a kind of trickster, he would get to be King for a single day at the annual Feast of Fools, a kind of parody of ecclesiastical ritual, and a kind of joke on The Fool, too.

The Crow complicates The Fool — Eric is still a fool for love, but he is guided doggedly by a singular goal in the way Don Quixote was guided by an absurd love. If The Fool is blissfully unaware, then Eric is untethered from any other consideration by his blinkered goal, caring for nothing other than his pain and Shelly and revenge. With his care for himself extending only to his psychic feeling, he neglects his bodily welfare, leaving it in the care of the Crow. He tumbles headlong into violence laughing maniacally and therefore terrifyingly. Certainly, O’Barr’s Eric and then Lee’s embodiment maintain The Fool’s sense of the comical — Eric cracks jokes left, right, and center, dancing and jumping around with a playfulness and mirth that on his sad figure scan as all the more garish and grim, all the more doomed.

Eric is aware of his forlorn, ridiculous position; in the way that The Fool has no grandiose aspirations, save for a singular day, Eric knows very well that he will never live alongside Shelly on the earthly plane, and will never celebrate their love. Nonetheless, he will take his day to seek revenge. Moreover, Eric is preternaturally intelligent, waxing comic or poetic every chance he gets, quoting Gothic and Decadent poets gleefully (Lee’s Eric deliciously quotes from Poe’s “The Raven” as he bursts through a pawn shop’s door), his moody, bleeding heart punctuating and pontificating as he rains bloody violence on the gang who wronged him. Through Eric, The Crow centers a traditionally ridiculous character, in a near affront to traditional masculinity.

In a sense, the Western world has Plato to thank for the values of traditional masculinity. In Republic, Plato theorizes an ideal society, and an ideal way for a person (read: a man) to be. Plato understood the human being as being guided, their life and mind, by a soul, which is divided into three parts: reason, spirit (those more amorphous and complex passions and emotions and drives, such as strength, anger, and ambition), and the appetite (direct bodily desires and needs, such as hunger). Every soul possesses the three parts, and in every person, one of the parts rules over others. In the ideal person, reason rules over spirit and appetite, keeping them in check, without the freedom to guide a body into an unsavory extreme.

Traditional masculinity is much indebted to Plato’s conception of the ideal person. Over numerous historical transformations and distillations and rationalizations, we have come to a cultural understanding of traditional masculinity as being all about rationality, stemming from the idea that the human being is distinguished from other animals by virtue of an ability to reason, the lack of which makes any being not a white cishet man a lower, lesser being. Traditional masculinity endeavors to repress all those elements that make the human being akin to other animals, such as unruly emotions and other passions. What is left is a clear, hollow, dry silhouette, a husk of a man who is logic personified in possession of a body that serves his reason. An embodiment of pure reason, he is all deadpan and observant, directed by science and objectivity. Because such a being is categorically not all that a human being is, we get toxic masculinity within patriarchy. Toxic masculinity is the result of the frisson between the way people are and the impossibility of achieving the ideal.

When a person believes that a clean, scientific ability to reason within deeply human circumstances is achievable and worth working toward, what is created is a hierarchy upholding unironically and dangerously the belief that anyone who cannot, will not, conform is lesser. An “other” is created — a group, a scapegoat in opposition to societal ideals who poses a danger to the ideal of ascetic being. People who are not white cishet men are simultaneously, paradoxically irrationally, constantly badgered to be traditionally masculine in this way, and also believed to be incapable of this thinking and being, and therefore the “other” is subjugated. This is why traditional femininity sees women as lesser and subservient — incapable of herself achieving the ideal, a woman’s singular goal becomes that of an aide, to help men work toward the ideal. Toxic masculinity tortures those trapped within its circuitous thinking, along with those “others” who cannot or will not conform. Cobain’s gender-bucking presence in the ‘90s, his heedless movement from the traditionally masculine to the “other’s” territory, his occupation of a space outside of or between the oughts and ought nots, was radical for this reason.

In The Crow, Lee’s Eric Draven dances maniacally on the grave of toxic masculinity. The film casts Eric as The Fool in a thick layer of irony, inspired by O’Barr’s deliciously macabre characterization. Eric is a fool with intense self-awareness by virtue of his intense and unchecked flow of feeling. Eric not only feels all his feelings, but we can see that he does. Lee’s performance has nothing restrained or antiseptic about it, he exuberantly shows us how much pain Eric is in, how much caring and love and anger he has within him on his body, through an honest and unpretentious, or hungrily hopeful manner of inhabiting his cruel world.

We are introduced to Eric through a kind of gruesome rebirth. He crawls out of his dark, sodden grave weeping, in his wedding suit that is torn, the tuxedo he was meant to be married in. He’s covered in mud that looks like oxidized blood, his dark hair long and matted and knotted around his face. Falling to his side in a fetal position, his eyes roll to the back of his head, and he lets out a blood-curdling wail, as though the mere act of breathing were as painful as the fatal fall he took out of his sixth-storey window. He stumbles back to the apartment he occupied with Shelly, limping, for his muscles might very well have forgotten the strain of life. Once there, he finds Gabriel, his and Shelly’s cat. When he touches Gabriel, memories of the night both he and Shelly were murdered strike him like a rushing train, and he keels over, physically living through that fateful night again, his body, though dead for a year, still carrying his memories.

Lee, in Eric’s rebirth scene, is a marvel to behold. Throughout the film we get flashbacks to the time Eric and Shelly spent together, what they were like when alive, what their dynamic looked like, what their love looked like. But Lee is so bewitching in the pain he feels at being alive without Shelly that the film could have been just as compelling without the flashbacks. Lee’s excavation of Eric’s wounds is earnest and acrobatic. If the realization and pain of having lost Shelly wracks him as violently as in this rebirth scene, if he is willing to hurt himself and to dole out the most brutal punishments to those who hurt him, then imagine how pure and perfect their love must have been. Imagine the beauty of the paradise lost that would warrant this kind of pain and havoc, Lee seems to say.

He shudders and weeps as he paints his face in the smiling mask of The Fool, the joker, cutting not so much a pathetic figure as a viscerally terrifying one. His first mark is Tin Tin (Laurence Mason). Where earlier Eric was hurled out of his home by T-Bird’s gang, as he approaches Tin Tin, Eric intentionally dives down a building, cackling all the way. Things start to become lusciously topsy-turvy. As he beats up Tin Tin, Eric becomes more and more disquieting, not because he can withstand the blows Tin Tin deals him, but because the only thing managing to hurt Eric are the memories of the fateful night that Tin Tin’s words carry. As Tin Tin lasciviously retells the events of the night, of the rape, Eric’s muscles tense up and he screams. There seems to be no point of mediation between a feeling flourishing or exploding within him and then appearing on his body — it’s all organic, un-self-conscious, without a thought to manipulate how others read him. While Eric certainly is in costume to reflect his inner torment, there is no artifice about him, no desire to manipulate others, to use or subjugate others in the way that others about him do.

In watching Eric’s interactions, both with friends and foes, I’ve always felt such a glimmering aura of safety emanating off of this tall, strong man, even when he leans into The Fool’s mania or wails as memories attack him. And I think this aura of safety about Eric stems from the honesty with which he wears his feelings, his fearlessness in appearing emotional in the way traditional masculinity believes women are. He is in pain, and all he wants to do is to feel better. In the comic, a couple of T-Bird’s gang stand in awe of Eric as he kills them — seeing as they do evident in Eric’s appearance the purity of his love and his pain, they stand abashed, feeling how awful Eric’s goodness feels, almost intuitively understanding that they have earned their demise. In the film, only T-Bird is brought to this sublime awe, and realizing the pain he caused Eric, T-Bird weeps, repeating to himself that singular line from Paradise Lost, “abashed the devil stood and felt how awful goodness is,” which he spat at Shelly before raping her.

There’s also safety in Eric’s lack of restrain, freedom and abandon. In the ways in which Lee’s Eric embodies traditional elements of The Fool physically, it’s very easy to see on his physicality how he is feeling, how beleaguered he is by his pain, or that he rejoices in a joke or dance because these joyous moments link him to Shelly. In other words, the ways in which Eric does honor traditional elements of The Fool, are also ways that allow him to manifest a safe masculinity. If toxic masculinity has a man stoically masking his feelings, methodically and rationally making it difficult to decipher his thoughts and empathize with him, then a soft masculinity is a certain freedom in feeling physically, extending cerebral, spirited feelings (bad or good) to the body and honoring them. Lee’s Eric frustrates traditional notions of the way a man ought to behave in the way that Cobain, uncaring of societal notions, did with his clothes (carrying his complex feelings about gender literally on his sleeve). For Eric, it’s not just his dark costume and make-up that mark him as uniquely different, it’s also his physical freedom to behave the way he feels, uncaring of societal notions.

Moreover, Eric’s goals are selfish, anchored in the undulating well of pain within him, which he wants T-Bird and his gang to feel, for they are the pain’s architects. And this pain ricochets off his bones and spills out of him through his perennially wet eyes. What is guiding him through the violence in this film isn’t something rational, not some reasoning as watertight as a mathematical equation; rather, it’s something as old as the Code of Hammurabi: revenge. Eric is guided by something as passionate and simple as an eye for an eye, something civilized, rational society considers barbaric.

I could go on and on illustrating why Lee’s Eric Draven is an enchanting force in this film, but I think I’ll cap it off with three scenes that best exemplify what I mean when I say that Lee’s Eric is picture perfect as he embodies a soft, safe masculinity by virtue of the complex emotions he so unpretentiously and freely and loudly wears on him.

The first is a comical scene, beguiling and jaw-droppingly beautiful for Lee’s performance in it. It is Eric’s visit to the heroin addict Funboy (Michael Massee), one of T-Bird’s gang, one of Shelly’s rapists, one of the murderers. Eric is a nightmare in this scene as he spills into Funboy’s room through a window, dragging his guitar behind him, calling for Funboy as though he were a rat to be exterminated. When Eric scratches his guitar’s strings to create a high-pitched dissonant scream, Funboy winces. It’s nails on a chalkboard to the high Funboy’s ears. There’s a flickering, exposed lightbulb hanging from the mess of the ceiling and Eric focuses his eyes on it and nudges it around with his forehead, like a madman, like the grim reaper. Then he flicks his eyes to Funboy, focused and lucid as a dream. He’d been playing a wraith, for he knew it would spook the dim-witted Funboy.

The gobsmacked Funboy shoots Eric repeatedly with a pistol. As Eric’s body ricochets around the room, he pretends to be in pain, and then, almost salivating at the spectacle he must be, he laughs in Funboy’s flabbergasted face as his wounds heal themselves. “Stop me if you’ve heard this one,” Eric inexplicably begins a joke, skipping before Funboy like an elated child. Later, he hops onto Funboy’s bed and sits cross legged, his hands on his ankles before him, like a toddler waiting for gifts on Christmas morning. Lee’s mannerisms here are brilliantly faithful to the Eric O’Barr draws out in the comic. Eric here is erratic, joyful, and basking in schadenfreude. But murderous and frenzied as he is, Eric cuts a safe figure because his violence is honed, determined and controlled by his blinkered and self-serving anger, which only wants to hurt those who hurt him. Moments later, he flicks to tenderness as he notices Darla (Anna Thomson) cowering in a corner, having witnessed all of Eric’s horror. Darla is mother of Sarah (Rochelle Davis), the street urchin who Shelly and Eric loved when they were alive. Eric immediately becomes kind but stern toward Darla as he tells her to go to her child, who’s lost and lonely in the city’s rain. Lee doesn’t play patronizing in Eric’s admonition of Darla — as he widens his round eyes as he tells Darla to go to Sarah, the skin around his eyes tightens, as if wincing, and it seems evident that Eric understands Sarah’s loneliness, and is working to protect her against it by sending Darla her way. This scene of tenderness with Darla shows Eric doing for Sarah what nobody did for him.

Lee makes a feast of this scene with Funboy and Darla, inhabiting it lithely and confidently as a dancer, with his whole being, armed with a deft understanding of Eric. How stunningly does Lee flicker between unhinged vengeance, playing with Funboy like a cat torturing a mouse, to tender care for Darla, an understanding inspired by deep empathy and love for Sarah. Lee is skilled-as-a-funambulist as he straddles the loudness of violence and molten whisperings of kindness, because he seems to understand the love that drives Eric, that even in a rampage, what is directing him is not an unchecked desire to cause havoc. Anyone who might think Lee wasn’t a skilled, dextrous, and shrewd actor ought to watch this scene. Never was greater sympathy and understanding displayed with such balletic grace. Never did an actor so thoroughly grasp and embody a character’s unique humanity. Not since Lee have I found an actor who could so nimbly dance between frenzied laughter and drool lewdly cascading from his mouth, salivating at the thought of hurting a bad guy, and the kind of willowy sadness that wrecks from within, making a mirror of his warm eyes.

All of Eric’s selfish and avenging violence in the film would not be possible without the purest, most devoted, gutting kind of love, the kind so beautiful and hungry one might be lucky to experience it at all, the kind that makes him forget himself completely, existing only for and with Shelly. Eric, in film and comic, would not be as nihilistically violent without the ability to love in the strongest, most self-abnegating way possible. He wouldn’t be as self-serving and as navel-gazing, prodding at his gash even as he fights and kills to alleviate its pain and his guilt, without a love that was so paradoxically selfless to begin with, the kind extolled by Aristophanes in Plato’s The Symposium, a myth that sees us searching for our other halves all our lives. It’s a kind of love that once experienced, never leaves the body. Even in death, Eric is capable of loving desperately and maniacally and unabashedly, as demonstrated not just through Shelly, but also in the bonds he comes to form with Inspector Albrecht (Ernie Hudson) and Sarah.

Albrecht was initially assigned to investigate Eric and Shelly’s murders, but was demoted for digging too deep and gleaning the truth, that nothing in the city gets done without Top Dollar’s say. When he catches a glimpse of Eric leaving one of his crime scenes, he begins to suspect something supernatural is at work. Sensing Albrecht’s goodness, Eric visits Albrecht at his home. “You’ve still got your hat on,” he tells Albrect. He hands Albrecht a beer from his own fridge, as if telling him to loosen up, before confessing to the confused inspector that he doesn’t know what he is. Though Eric knows he is a Fool in the film (earlier, when Sarah asks Eric if he’s supposed to be a clown, he says that sometimes he is), Eric is not entirely clear on what kind of an entity he is, metaphysically.

Eric touches Albrect’s head and his body is immediately flooded by everything the inspector witnessed with regard to Shelly: her stay at the hospital after the attack, the thirty hours the doctors spent trying to save her life; Eric feels all the hours of her pain. Albrecht remembers it all, and is able to give the pain to Eric. Eric falls to the floor gasping from the ache, and as he gathers himself, he notices a framed picture of Albrecht and a woman. It’s Albrecht’s soon-to-be ex-wife. Eric plucks the cigarette Albrecht’s just lit up out of his hands, and, taking a deep drag, says, “You shouldn’t smoke these, they’ll kill you,” with a smile glinting in the tears in his big hazel eyes. Eric intimates that he used to smoke, but gave up for Shelly — little, trivial things used to bother Shelly, he explains, but these things are never really little if they mean something to the person you love.

Eric doesn’t make any grand pronouncements in this scene, he just visits a man he met only in death, a kind face who could explain things to him, who could give him Shelly’s pain. It’s a raw scene that never fails to make me cry because of how small the mighty Lee looks here, sodden with the perennial rain that might as well be a lifetime of his own tears. Lee gives us Eric unmasked, molten and full-bodied, what he might have been like in moments of calm during life; he gives us the vulnerability, the humanity that allows The Fool to so successfully be the protagonist in this film.

In the terrible sequels for this film, scripts and actors inexplicably latched onto a single aspect of Lee’s Eric — Vincent Pérez in City of Angels gives us only the tragic, quixotic romantic without any sense of humor; Eric Mabius in Salvation offers us only the calculating and vengeful figure, closer in kin to traditionally masculine characters vis-à-vis how rational his Crow is; and Edward Furlong in Wicked Prayer gives us the comical Crow that is pure Fool, feebly attempting at the charm that Lee was able to infuse his dimensional Eric with and becoming a tertiary character in his own film. Lee is the only one who is able to offer us humanity — a man aching, tender, angry, kind, complex, hoping for salvation in hopeless circumstances. A man so much like the image of tragic hopefulness Cobain offered us.

And it’s his variegated humanity, the pain he’s collected over the course of his night, his roiling emotions like churning lava, that Eric is ultimately able to use to gain a semblance of a victory against Top Dollar. In chasing his final mark, Skank (Angel David), he wanders into one of Top Dollar’s meetings, a kind of sabbath of goons. Skank has taken refuge there. Eric interrupts Top Dollar’s screed about how defunct Devil’s Night has become to say that he doesn’t care about any of them, he is just there to collect and punish Skank. Eric only ends up killing all the bad guys because they won’t let him leave with Skank, rather incidentally. This scene perfectly embodies Stratis’s point about Cobain: Eric isn’t angry at Top Dollar, for he doesn’t know yet that Top ordered that he and Shelly be disposed of; he is rather doing the only thing that might allow him some sense of control over his own pain, his curious position — half alive, half dead — within the world, which is the simple act of killing those who killed him. Eric categorically doesn’t want to fix the city that destroyed him. It’s rather revolutionary Eric manages to keep the purest kind of love alive in a cruel world even after death, rampaging through it with nary a desire to play by its paternalistic, bureaucratic rules. Like Cobain’s, Eric’s anger is about himself, it doesn’t lead to a desire to fix the city that’s under Top Dollar’s sway.

The film paints a deeply intriguing contrast between Eric and Top Dollar. The latter is cool as a cowboy. But he also is charming and cracks jokes in the midst of battle in the way Eric does. What sets the two apart is Top Dollar’s steeliness, his ability to turn off his sadness at the drop of a hat, and the joy he takes in violence for violence’s sake. In the film’s final moments, Top tells Eric that the order he gave to have him and Shelly killed, their apartment cleared — it was nothing personal. It was just business, Top’s skewed form of bureaucracy. This impersonality is what sets him apart from Eric.

Because the thing is, Eric possesses an indelible and integral goodness, a humanity that is apparent in him before he becomes “The” Crow. In the way that Cobain was always a feminist, Eric was always a fool for love. In one of his flashbacks to normal, alive times, we see Eric in Shelly’s arms asking her to tell him again and again that she loves him, just asking her to repeat the phrase over and over. A sleepy smile spreads across his face, closing his eyes in a blissful sleep. We also know Eric was good in life through Sarah, who remembers his kindness. Eric never hurts anyone who doesn’t deserve it. He is reborn with his moral sensibility intact, his desire for love, his all-encompassing love for Shelly. He’s so kind and gentle toward Gabriel, feeding him, petting him with a tender caress. This is a good man, warm with passions, unlike the cold, ambiently rational Top Dollar, who conceals his feelings and plays mind games with everyone about him.

It’s because of all of this that I would be wary of calling Eric Draven, at least Lee’s portrayal, a superhero. There’s nothing stoic about Eric, nothing supremely moral and insistent on goodness, on manifesting it in society. Because Eric is so fucked up internally, and everything he does is so that he might feel closer to Shelly again. Despite all his goodness and love, he still doesn’t possess the egoic placidity of a saint, which the quintessential superhero does, because it’s what allows him the moral ground to insist on goodness within the society about him. Even Batman, tortured as he is, is so essentially the austere, traditionally masculine figure, commanding of others that they behave rightly, despite the pain he feels, instead masking it and eliding himself and his own wounds. Eric excavates his wounds, shows us his bleeding scars and wails from their slicing hurt.

Near the end of the film, Eric has a conversation with a weeping Sarah. Throughout the film, Eric has been running into the child as she skates through the decrepit and grimy city that is so inhospitable. Before the film’s explosive denouement, Sarah is sleeping on Shelly’s grave. Eric nudges her awake. He sits cross-legged before her, his hands on his ankles again. His frame, which earlier loomed and towered as it doled out punches and threw blades that stuck in arteries, seems small, as small as Sarah’s frail, emaciated frame, small in the way Cobain often looked as though swimming in his cardigans. Sarah is weeping, Shelly and by extension Eric were the only kindness she ever received in her life and she misses Shelly endlessly. When she tells Eric that he left her without saying goodbye, that he died without saying goodbye, Eric’s eyebrows knit. Her words have pained him.

“You’re just gonna have to forgive me for that,” he says in a voice that is small and soft, as if straining to keep a boulder of a wail within his throat; it’s a voice so unlike the robust cackle that erupted from him before he killed Tin Tin, so unlike his screams that feel like skin grating against gravel. While earlier Lee’s Eric’s voice was febrile and volatile, wide and vibrating with wrath, here it falters and feels heavy with sadness, hushed like he’s talking through a mouthful of cotton balls. This scene never fails to move me because of the closure it offers that, though full of love, lands like a blow to the gut, brooking no contradiction.

The pain in Lee’s voice as he utters the phrase, the way his eyebrows furrow and the skin around his eyes tightens, the way he almost seems to wince as he conveys the knowledge to Sarah, speaks to Eric’s intense guilt and grief. The line doesn’t carry any profound knowledge, and in less capable hands could have been conveyed rather flatly. But Lee’s delivery is so understanding and sympathetic as to endow the phrase with the heft of a salutary verse; he turns the phrase into an honest truth that he knows to be prickly, for Shelly left him without saying goodbye, too. When revenge has been achieved, forgiveness seems the only way to survive. “And you’re never coming back,” Sarah responds, and Eric doesn’t know what to say, so he smiles a sad smile, and gives Sarah the engagement ring he gave to Shelly. When Sarah hugs him with tears streaming down her face, Eric trembles — he can still feel others’ pain through touch.

However much Cobain’s public image may have concealed about his private self, what we did get was his honest fallibility, fearful hope, and hopeful anger, which defined an era. Lee preternaturally managed to to deliver a stark iteration of the Cobain image through a dimensional performance whose resounding pain and love few have been able to replicate with as much skill and feeling.

Do I look civilized to you?

It would perhaps be an essay unto itself — and perhaps an argument made many times before — all the ways in which the Chad Stahelski- and David Leitch-directed, Derek Kolstad-penned John Wick is a near retelling of The Crow. The two share the same understanding of the function of memory and photographs, share a quixotic love for a woman with a literary name, a reemergence from the grave. Even David Patrick Kelly makes an appearance. Much in the way of John Wick’s iconography recalls The Crow. But what makes the film its own unique and marvelous entity is John Wick himself, or Reeves’ characterization of him.

Where Lee’s Eric is flamboyant and erratic, embodying a loud and soft masculinity, dancing and cracking jokes and quoting Gothic poetry, Reeves’ Wick is demure, still, and pensive. Ostensibly, John Wick is very much the picture of traditional masculinity — not saying much, John is pure action, pure will directed at a goal, calculating and seemingly mechanical. But I would say that there’s something else, something riotous and molten, going on here, with Reeves’ portrayal and with the story itself.

The film’s plot is very simple: John Wick comes out of retirement after his puppy is killed and his car is stolen, to punish those responsible. John is enraged because the puppy was a gift delivered to him from his wife who passed away from cancer mere days earlier. And while this film, like The Crow, is impossibly cool, casting Reeves as a sexy assassin who, unflinching and uttering very few words, effectively achieves his goal; while the film does seem to cast Reeves as the picture of the repressed and traditionally masculine man, I would argue that John is in actuality a variation on the Cobain ethos. Though flamboyance isn’t John’s style, he is still, in his own Reevesian way, very emotional. I would say that much like Cobain and Eric, all John wants to do in this movie is feel, he wants to process grief and wants hope, and when an annoying brat gets in his way, all he wants is revenge. Like Cobain and Eric, all John does is in service to what he desires.

Very early on in the film, Viggo (Michael Nyqvist), lead of New York’s Russian mafia and father of Iosef (Alfie Allen), the young man who kills John’s puppy and steals his car, calls John. John is in his basement galvanizing his old life. In the way that Eric bursts through wet earth and is reborn in The Crow, John spearheads his own rebirth by cracking into the ground and digging up his weapons and clothes from his assassin days, which had been cast in concrete in his basement. “Let us not resort to our baser instincts, and handle this like civilized men,” Viggo says with calculated calm to John in a desperate attempt to save his son. Viggo knows very well that John intends and will succeed in killing Iosef. Without uttering a single word, grunt, or breath, John hangs up. John will not be civilized.

Later, at the hotel Continental’s bar, John sees Addy (Bridget Regan), a bartender he knew in his working days. “I’ve never seen you like this,” Addy says to John. “Like what?” he asks, puzzled. “Vulnerable,” Addy says. Indeed, John has been moving through the film thus far as though sodden with tears, with a glint in his eyes that isn’t so much menace as it is memory of Helen, and his silence seems to express irritation at not being allowed the space, time, and solitude to think only of her. In addressing Addy, a soft smile buds on John’s face, but it doesn’t bloom big, as if his body isn’t yet ready to feel such a grand gesture for the pain it might ignite through memory work. Reeves has always excelled at massaging depth — pain, sadness, anger, love — into a character’s contours while maintaining a heavy stillness, understanding his characters’ limits.

While John certainly has few lines in the film, Reeves is still able to tell us John’s story through his warm, teary eyes, their silent observing, his furrowed brow, the set of his jaw, his voice that snarls and roars or becomes delicate as it feebly remembers past friendships, and the particular swiftness of his movement, which seems to be necessitated so as to keep sobs from wracking through his body. Here as elsewhere, Reeves masterfully conveys his character’s humanity through a bracketed, hushed screen presence, a deft understanding of his form and the body’s ability to convey feeling. John isn’t a robot, Reeves shows. Through subtleties that are buttressed and punctuated by explosions of white-hot anger, Reeves allows John to emerge as a man honoring his feelings, wanting mightily to process his grief.

In a scene that is a direct corollary to the one in The Crow where Eric walks into Top Dollar’s board meeting asking for Skank, John confronts Viggo, and says to him, “Step aside, give me your son.” John doesn’t want anything from Viggo — all the violence he does to him and his henchmen is always in retaliation, in response to Viggo’s derailing or obfuscation of John’s plan to kill Iosef. Like Eric, John doesn’t care to make a point about how mafiosos are running amok in his world, he doesn’t care to fix the system that birthed an entitled, violent man like Iosef. So much of this film is ambient anger to do with the loss of Helen, and Iosef and Viggo are mere attempts for John to find steady ground, and are channels for the processing of his anger and sadness.

When Viggo asks John why he won’t just let his son go, says that it was a mere dog, a mere car, we see John deliver us the reasoning behind his madness that Reeves has already conveyed to us through his tears, his clutching of Helen’s bracelet, his endless watching of a video he filmed of Helen soon before her death.

John says that when he received the puppy the night of Helen’s funeral, he found hope. “In that moment, I received some semblance of hope, an opportunity to grieve unalone,” John says. “And your son took that from me. Stole that from me. Killed that from me. People keep asking me if I’m back, and I haven’t really had an answer. But now yeah, I’m thinking I’m back. So you can either hand over your son. Or you can die screaming alongside him.” John veritably growls the latter half of his short speech, and when he says “took that from me,” he sounds like a feral monster. It is the most terrifying Reeves has been on screen, his already deep voice becoming hellish, like a blade against brimstone.

This confession, fired at Viggo not so much like daggers but like hellfire, coming from the roiling anger within John’s belly, from that spirited place, as Plato might call it, of anger and unprocessed grief — all this speaks to John’s intense sadness and fear and ire, and loneliness. All this speaks to everything messy and passionate churning within him unresolved, everything that traditional masculinity might require of a man that he never let show to others. John’s confession is aching, honest, and allowed to burst forth from him in desperation. It’s emotional and turbulent and unhinged, everything that the traditionally masculine man is not.

“Do I look civilized to you?” John fires at the film’s end as he kills Viggo, a kind of belated answer to Viggo’s earlier plea for civility and rational behavior. The rampage that this film charts is John’s attempt to rebuild hope after a world-shattering loss. Later films ask John where his rampages, inspired by various motives for revenge, will stop. I think John would know that revenge doesn’t solve anything, that it will not magically bring Helen back. But it is action at all, and to anyone who has been so profoundly hopeless as John feels in this first film, John’s action’s scan as meaningful because they are inspired by the intuitive knowledge that even irrational actions are better than nothing. Even if ultimately John’s revenge is futile, even if it is mere thrashing in an uncaring world, it helps him to feel better for the moment, for through its enactment it honors his feelings and desires.

John retains a wound early on in the film as he hunts for Iosef. It’s on his abdomen, doled by a henchman who drives a broken champagne bottle into his gut. Throughout the film, various adversaries repeatedly hit John in that wound so as to debilitate and momentarily overpower him. But at the film’s end, in a battle against Viggo, who John is angry at and seeking to kill as a way to avenge a friend’s death, John uses his wound to his advantage. Viggo has a knife poised before John’s wound, and, so that he might be able to overpower Viggo, John pulls Viggo’s hand and knife into his abdomen, stabbing himself. Viggo is taken by surprise. It’s a totally insane move, and as he scowls from his pain, John looks terrifying and beastly. Reeves’ expression on John’s visage is of the same sort as Eric’s maniacal laughter in Funboy’s face as the bullet holes in his hands heal — if a man welcomes this kind of pain, smirks in its face, then imagine how terrible the pain must be that makes him weep.

In the film’s final moments, we get a tender vignette, but even it reveals something desperate and hungry in John, something that has been looming larger and larger throughout the film. The toll a lack of a healthy grieving process takes of a person becomes most evident in this scene. John stumbles into a dog shelter, and as he staples the wound to his abdomen, he notices a pitbull marked to be put down. He staggers over to the sweet dog. In a voraciously hungry way, John reaches for and guides the dog out of his cage. “C’mon, let’s go home,” he says, and the dog trails after him. This pitbull isn’t a beagle like the one Helen sent to him, and it’s a boy, an adult boy, not a puppy like Daisy.

It’s heartbreaking, this grasping for some semblance of Helen at all, and in this scene, this denouement, Reeves stunningly portrays in his mesmerizingly still way a kind of clawing desperation in John Wick, how terribly he needs hope, how the only way he can now get hope is to build it for himself. Though this end certainly portends healing for John, there’s something about it that makes me immensely sad. It depicts what Stratis writes about Cobain — it’s a frustrated attempt to seek control over his own situation. Having lost Helen and Daisy irrevocably, he gets another dog, any dog at all, to bring him back to the moment of first receiving Daisy and hearing Helen’s voice in the note that accompanied the puppy.

So much of Reeves’s John Wick is weeping and sodden with tears like Lee’s Eric is. John’s determined veneer carefully contains and reveals a churning and roiling madness and pain that we catch glimpses of not only in his burning eyes, but also in the heaviness with which his deathblows land, in the ways in which his voice growls, roars. So much of Reeves’ characterization of John provides us with a figure in a state of lack, as opposed to the self-sustaining completeness and steadiness of the traditionally masculine man who is trained to be an island. With John we get a human, a person warm and confused, a man who freely acknowledges his need for others, for Helen, for Daisy, for his new pitbull.

There is nothing at all robotic about John Wick; rather, he is just as passionate and sad as Eric, as Cobain, as angry as them, though in his own, uniquely heartbreaking way. Wick easily acknowledges that he needs help to grieve, to process his loss; it’s an acknowledgement of his pain, that he is in pain at all, as opposed to ignoring or repressing it. Acknowledgement of pain means a realization that something is wrong and needs attention, which men are not brought up to vocalize. It means he wants to get better again, it means he has hope that he can get better again. Even if he might not be certain, he at least has his dog as evidence that he attempted to feel okay again, to retain some control.

This place hurts worst of all, doesn’t it?; or, I’ll abort Christ for you.

To me, these stories feel a bit like flailing and screaming and panicking in a vast body of water, and others can see, but no one is either looking, or cares enough, or is equipped to help. Lisa Whittington-Hill, in a piece from 2019 making the case for why Courtney Love deserves to be the girl with the most cake, cites a moment in Montage of Heck. It’s a moment from a home video. Cobain is holding an infant Frances Bean as Courtney hovers about the two looking for a pair of scissors. Frances is to have her first haircut. Courtney had earlier called Cobain in from the balcony, where he was moving around as if in a stupor. Holding Frances, he says he is just tired, but “it’s clear he’s not,” Whittington-Hill writes. Many times, it seems as if Cobain will topple over with the baby in his arms, and as Courtney carefully cuts Frances’ wheaten locks, no one, least of all the person holding the camera, acknowledges Cobain’s state.

Whittington-Hill’s piece explicates how the press in the early ‘90s indemnified Love, casting her, as the media often does with women, as the one responsible for all Cobain’s troubles. “The scene is a reminder of how the press treated Cobain’s addiction when he was alive,” Whittington-Hill writes. “They just carried on like nothing was wrong, instead directing all their judgment at Love.” No one noticed Cobain flailing, no one cared to help, in part because of misogyny, in part because of prejudiced and bleak understandings about the workings of addiction. Cobain truly in vain attempted to pinpoint all the things internal that “felt out of step with the world around him,” and no one cared to notice, until it was too late, at which point he was deified. What I hope to latch onto are Cobain’s deeply human passions, deeply contextualized, even if ambient and amorphous, frustrations at an impossible world, which all so strikingly subvert our understandings of gender and what it means and looks like to feel so acutely.

When I think of Cobain with Stratis’s understanding, I feel about him an ethos or an immense sense of fluid freedom commingled with an impossible kind of sadness, both of which only The Crow and John Wick have been able to convey to me since reading Stratis’s essay. I’ve been watching The Crow a lot lately, and until recently I couldn’t ascertain why. Certainly, it’s because of Lee’s handsomeness, I wouldn’t pretend otherwise. But there’s something else about the film, about Eric Draven, something I found in O’Barr’s original comic, that I have attempted to communicate in this essay, something I can only compare to the feeling of waking up with swollen and raw and red eyes after a night of crying. It’s the weight of feeling so much and all in isolation, the kind of isolation of Eric’s death, the kind of John’s grief, the kind of Cobain’s diary entries. Waking up in the morning after a night of feeling everything from anger to sadness to powerlessness to abject hopelessness, to a morning where nothing has magically changed. On such mornings, my mind always manages to proffer a rhetorical question in the dust lazily dancing in the pale sunlight: what if today is a balm? This is what The Crow and John Wick and Cobain communicate to me.

That the John Wick franchise, this grand and violent series anchored in a deeply, profoundly sad and angry and lonely and passionate character, has captured our imaginations so beguilingly, perhaps means that we, too, feel hopelessly angry in face of an uncaring world. The grunge fashion aesthetic has been gaining purchase recently, for various reasons, but what if John Wick’s popularity among audiences, though certainly to do with its having been brilliantly crafted, also has something to do with so many of us finally feeling the kind of anger and frustration the prescient Cobain felt 30 years ago. Perhaps these films containing nuggets of deep loneliness and intense striving against it, a kind of vain honoring of the self and its emotions, have been able to scratch an itch that could never be scratched by the abundance of extremely capitalist and pandering mainstream superhero films.

This is by no means to say that Cobain, Eric, and John are saints for the simple act of feeling, but they are doing something compelling and revolutionary for feeling within our clunky and unfair world. Indeed, Cobain notes the paralyzing heft of empathy, and for both Eric and John, feelings carry the weight of a plague, torturing and wrecking their persons. But despite the weight of the pain of feeling, these men stand for a persistence in feeling, evidently and acutely.

Cobain acted as he felt, and thereby fucked with the system. As Stratis writes, Cobain pushed the boundaries of gender by being “so loud, and so angry,” going on to ultimately push “for the very things we pushed for ourselves.” Eric and John Wick embody the image that Cobain finessed and presented to the world. The two characters are so quintessentially grunge that, guided by their unchecked feelings, they (these male characters read so often as macho, superhero-esque) end up presenting to audiences a safe alternative to toxic masculinity. They possess the kind of vulnerability and softness that Cobain publicly reveled in, as they both work to help themselves feel better, find elusive control over themselves and their place in the world, working, even if impossibly, to find balm. In their unbridled and unabashed feeling, in their being in themselves, they simply don’t have time enough for, nor care to consider notions of cultural rightness or wrongness.

On all three of these men, on their bodies and in the timbre of their voices and in their wet eyes, it is evident they have experienced the feelings of another, the kind of love and empathy that is all-consuming, and they weep because, in the face of a world willing to destroy this beauty, they are willing to destroy themselves to preserve their own private beauty. This is what grunge is, at least, what Cobain’s grunge was — an effusion of feeling, good and bad and fear and love, within and against a world unafraid to snuff everything out.