Reality, obliteration, and (un)certain futures in Miyazaki’s ‘The Boy and the Heron’

Hayao Miyazaki’s latest film explores reality itself as a constructive and destructive force on our bodies, lives, and psyches.

There is no shortage of merchandise of beloved Ghibli characters—from playing cards to bean bag chairs, you could easily outfit a house, if not an entire life, with products that remind you daily of cozy scenes from your favorite Hayao Miyazaki films. Studio Ghibli movies seem to often inspire this feeling, of wanting to bring the magic from the film into our everyday lives, to not forget the emotions brought on by the film. Similarly, scenes from The Boy and the Heron remained in my mind for many days and weeks following my viewing it. But rather than stir up feelings of whimsy or fondness for the recent film, I often felt oppressed upon remembering it, or paralyzed by dread when thinking about the film’s opening and final scenes. There is something different about Miyazaki’s latest film. It is shocking in a violent way. In a horrifying way. In a haunting way.

None of this is to say Miyazaki’s films have always been purely whimsical and innocent in their content. My Neighbor Totoro contains obvious references to nuclear war. Howl’s Moving Castle contains elements of time distortion due to the traumatic effects of ongoing war and violence. Many of Miyazaki's other films are about the catastrophic nature of human greed and development. What makes The Boy and the Heron different from his previous is his treatment of reality itself as a corrupting force on the film’s characters and ostensibly the “you” in the Japanese title of the film How Do You Live (i.e. us, the viewers).

Let us begin with noticing a unique facet of the entrance to the “magic world” or “dream world” in the movie: it is an entrance. In other Ghibli films, magic spirits coexist in the same world as humans or can move freely between their world and the human one. In My Neighbor Totoro the Kusakabe sisters, after Mei first ventures into the forest and encounters Totoro, encounter spirits of the forest throughout their daily lives in their small, bucolic town. In Princess Mononoke and Nausicaa and the Valley of the Wind, humans actively fight against fantastical life forms from nearby forests as they seek to expand or solidify their civilizations. Even in Spirited Away, where the spirit world must be accessed through a portal, the spirits in the said world interact with the everyday one of humans; Haku, the spirit the protagonist Chihiro frees from enslavement, is the spirit of a river in the human world that rescued Chihiro from drowning when she was younger. The borders between these worlds, if in existence at all, are malleable.

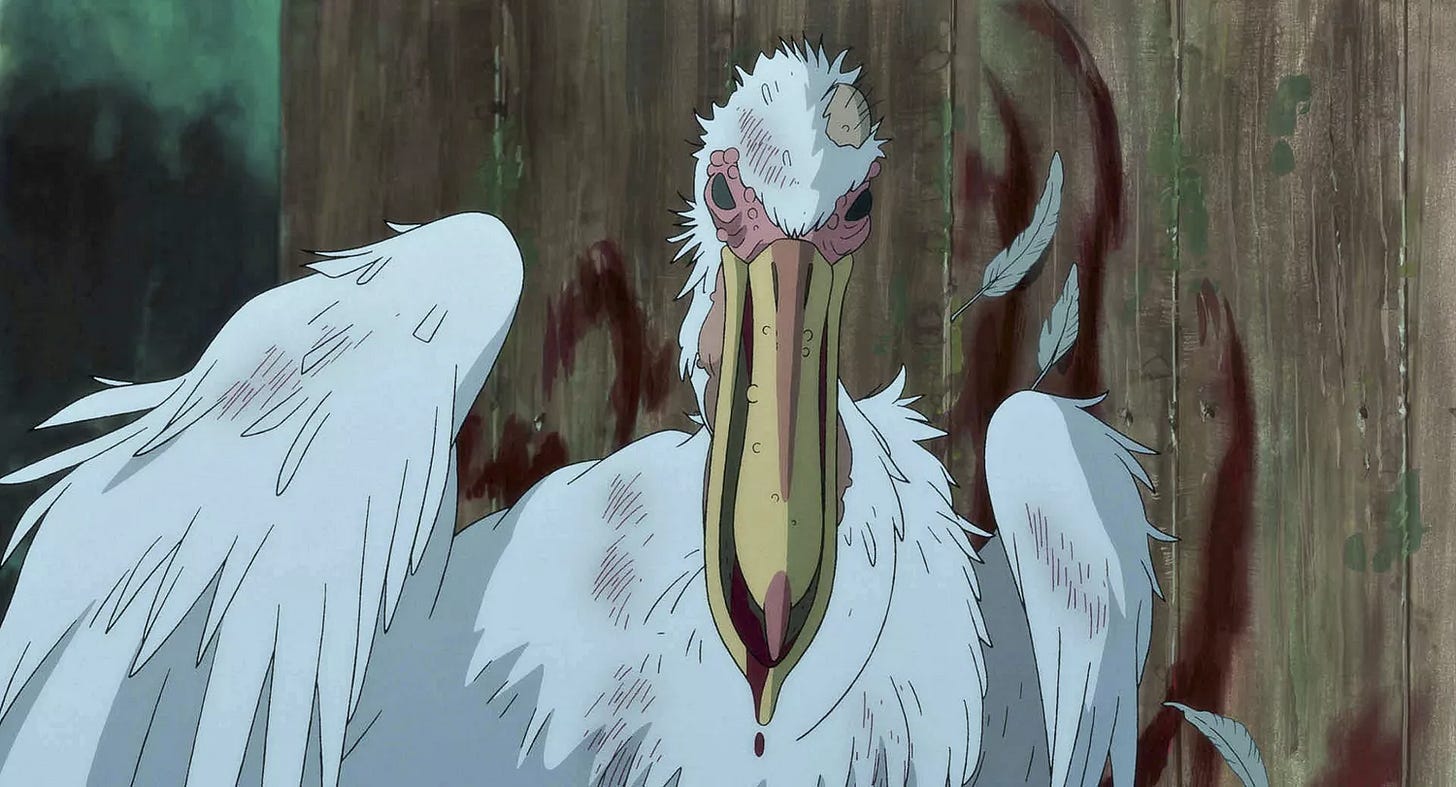

Conversely, the magic world of The Boy and the Heron is itself hostile to humans. In other Miyazaki films, spirit worlds have been indifferent to mankind and placed them on equal, if not lesser, ground than other forms of being, but they have never aggressively depended on their exploitation and slaughter for their existence. The same cannot be said of The Boy and the Heron. Consider some of the most haunting sequences of the film: Mahito bound in chains by a hungry murderous bird, sharpening a butcher's knife on a table surrounded by cuts of fermenting meat (ostensibly, other slaughtered children). A parade of birds cheering for a child being carried through the crowd in an open coffin, voices ringing out in praise of their king. A pregnant woman kidnapped and imprisoned in a dark, solitary cell for the harvesting and sacrifice of her infant child. The malice that infests this world is not an unfortunate by-product of a certain civilization but rather the very reason for its existence; in other words, its fuel.

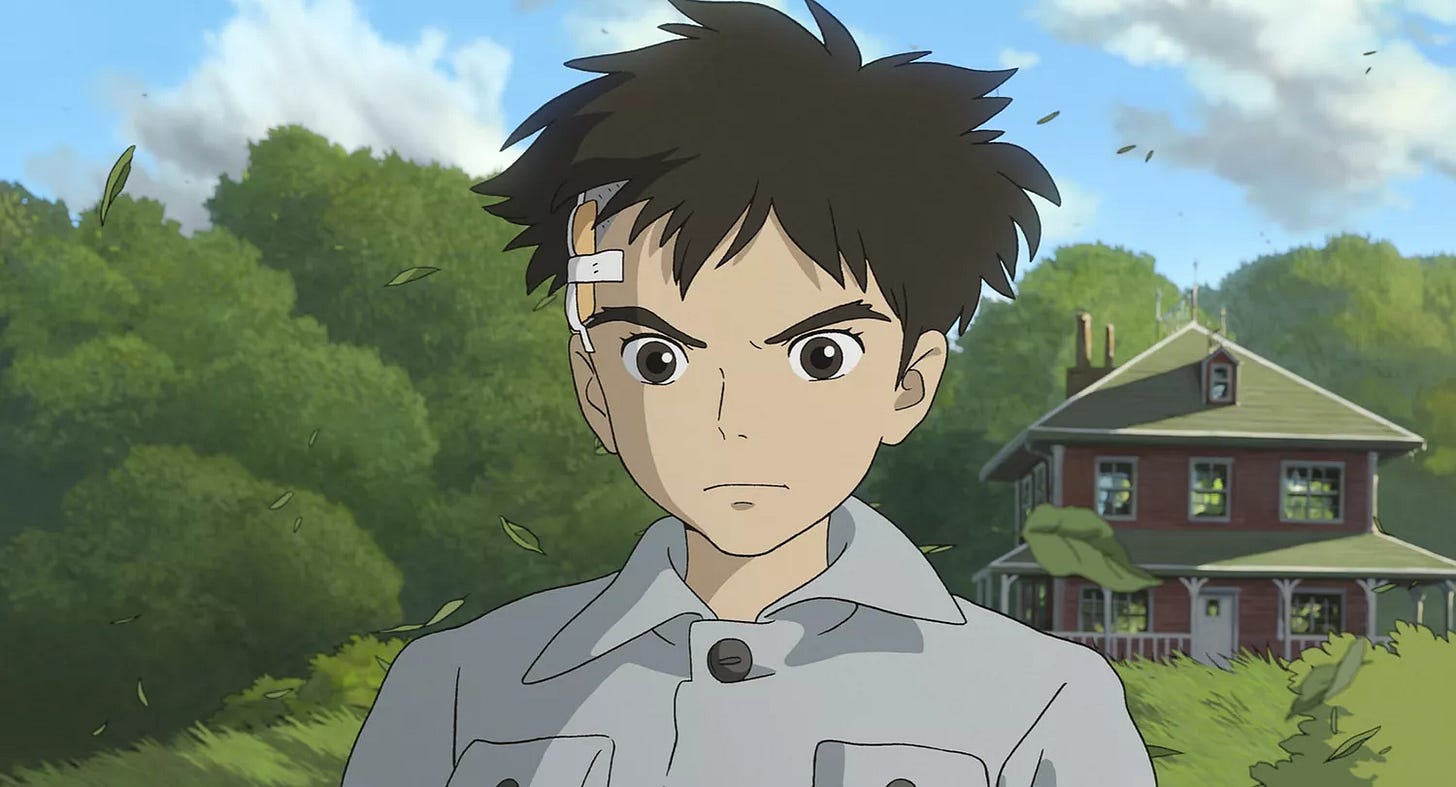

The bird-dominated world lies behind just one of an infinity of doors Mahito can open in the tower. We don’t get a glimpse into many of them, we just know they are there, marked by non-sequentially numbered doors, yet another indication that the world of the tower is not governed by the same logic as the human world. The only other world amply explored in the film is Mahito’s original world, Japan during World War II (in other words, our world). Similar to how the bird’s world is predicated on the suffering and extermination of humanity, the film explores what our world relies on for its existence, how reality destroys and rebuilds us, how it molds our pasts, presents, and futures. Beginning from the film’s opening scene of the firebombing of Tokyo, it is clear that this world is one that viciously tears apart families, individual realities, and innocence. It drives Mahito to express his rage at the world by mutilating his own body which, rather than assuage his frustrations, only continues to fuel his anger, his face twisted into a near-permanent grimace for the rest of the film. He is not curious towards the supernatural as other Ghibli film protagonists have been; his first reaction, upon meeting the heron, is to try to shoot it with a bow and arrow.

Mahito’s self-directed attack is only one example of several responses to the state of the world different characters display. The elderly women of the estate Mahito evacuated to with his father retain brilliantly depicted personalities, each deftly differentiated from one another through their humor, fashion sense, and animation of their walking style. But when Natsuko brings a suitcase full of cans of imported food from abroad, they all crowd around and swarm it in the same way, overjoyed to see all the new, exciting goods. Stripped of their individuality, the elders are reduced by their desperation, and Mahito seems disgusted with their behavior. The women of the estate have survived through a world war marked with widespread death and starvation, and have witnessed the death of the eldest daughter of the estate and taken in her surviving family as the firebombing of Tokyo forced their exile. It is not in spite of the metaphysical injuries these devastating events caused that they are so eager to indulge in consuming these foreign goods but because of them. Perhaps at a younger age they could have held a grudge against war like Mahito, but that flame has long been extinguished inside them by reality. They have had to fully adequate themselves to reality in order to survive and in the process lost something valuable: a force within them telling them that the way they are living isn’t necessary, that there are other ways to live, and that even if they cannot be obtained their existence should be known and striven toward.

The struggle between the individual and the force exerted upon them by reality is not unique to the human condition. It is not from a failure in ourselves but from the oppressive nature of existence that our lives and latent potentials are obliterated, as shown by the trope of the transmutation and metamorphoses of birds throughout The Boy and the Heron. As previously noted, the parrots occupy a particularly morally abhorrent position in the tower world, relying on the exploitation and slaughter of children to fuel their society. Yet when Mahito opens the door to his reality and the parrots stumble into it, they shrink, transforming into harmless parrots that seem content to fly about and sit on people’s shoulders. Their former existence is neutralized and eliminated and a new once is forced upon them by the new reality they enter. Pelicans are spared the physical transfiguration but undergo a dramatic change in their means of survival; when forced into the world of the tower, they resort to eating the souls of the unborn to sustain themselves. They are not able to escape their new world, and must choose between three prescribed fates: starvation, consuming souls, or death by the fire of the pyrokinetic Himi. Reality eliminates any potential for the pelicans to exist devoid of malice, as it forces their existence to inherently be malicious. Any pelican who cannot perform malice or refuses to be consumed by it, such as the noble pelican Mahito encounters, are obliterated. The world constructs a reality in which no pelicans can exist devoid of malice.

Reality molds bodies as much as it molds the nature of existence in The Boy and the Heron. There exist no ways to jaunt between worlds as there were in past Miyazaki films: each distinct reality branching off from the tower is set behind a door that, once opened and stepped through, cannot be returned through. Even the possibility of knowing that other realities exist is destroyed at the end of the film by the collapse of the tower; the oppressive nature of the world aggressively eliminates any alternative forms of existence. The story follows Mahito as he navigates what it means not just to confront this reality but to be brought up by those who have adequated themselves to it, surrounded by evidence of his predestination to accept it. Adjusting to the world quite literally runs in Mahito’s DNA: hit father is an arms producer, contributing to the war and violence that killed his wife, perhaps even producing the same type of munition that killed her. Not just accepting but fueling the reality that tears him, his family, and his world apart is preordained by the blood that runs through Mahito’s veins.

Mahito’s self-inflicted head wound initially seems to be the physical embodiment of his adequation to the violent ways of the world; he points to it as evidence that he possesses malice when speaking with the wizards in the closing scenes of the film. Mahito shows a remarkable ability to adapt to all the realities he encounters in the tower. When seeking help from the giant parrots to find his stepmother, Mahito seems as unphased when they speak to him as when he realizes they are encircling him to prepare and consume him. He is similarly unperturbed when he discovers Himi’s unique ability to teleport and travel the world instantaneously through fire. When encountering other unknown anthropomorphic creatures, he shows little reaction beyond mild suspicion and guarded behavior, a guard that can be let down when he comes to love and trust someone (such as Himi or, shockingly, the heron, who he refers to as his friend by the end of the film). He seems readily able to accept any reality and adjust to it. Yet Mahito still chafes at the reality of war-torn Japan. He cannot stomach his father’s moving on to another woman in the wake of his mother’s death, his steely gaze constantly upon the pair after their evacuation to the countryside. He is disgusted with the ease and speed with which the inhabitants of the estate forget what was lost in the war and jump to consume tobacco and imported goods. In this context, Mahito’s self-inflicted scar is less a testament to his being infected with malice than it is to his repugnance to his being so. He sees the evidence of humanity’s being equated with malice in the world, just the pelicans are in the tower, and witnesses it befall him as well. It is this anger, which takes root in his inability to adequate himself to his existence, which enables Mahito to keep a clear vision devoid of malice for the future. Right before the tower’s collapse, Mahito turns down the wizard’s offer to restructure the blocks that balance the world, pointing to his scar as evidence that he has already been damaged and thus cannot produce a benevolent world. However, this scene is interspersed with cuts to a vision in his mind of a stable arrangement of the blocks. Mahito can have hope even without innocence, a hope which resides in his outrage towards the world.

In the closing scene of the film, Mahito’s family beckons to him as they step out the door of the countryside house, all dressed and prepared to return to Tokyo. Compared to the rest of the film, the time between the fall of the tower and the family returning to Tokyo is quite compressed. Mahito walks back from the tower, happy to have survived its fall and rescued his step-mother; the film then immediately cuts to him packing up his belongings and hearing the calls of his family, with Natsuko’s newest baby in tow, to come downstairs. The film ends with a shot from his view, looking down at them from the top of the staircase. His gaze lingers on them as they begin to leave. There is something within Mahito that prevents his seamless transition from this life to the next, from moving from the past to the future, to participating in the progress of the world and yielding to the pull of time. It is the beauty and importance of this hesitation that Miyazaki crafts through The Boy and the Heron and directs a final attention to in the closing of the film.

Reality is arbitrary. How the reality of our world channels our latent potential is a process the film urges us to consider. A soul, a form of existence, can in this life be an old woman and in another be a masculine warrior-pirate. Birds that feed on dead children in one world turn into harmless rainbow parrots in this one. Fire, in one world a symbol of purity that Himi loves and admires, is the force that kills her in Mahito’s. The question the film urges the audience to consider is how to conduct oneself given the forces of our reality on us. It is a non-negotiable issue, as the ending sequence of the film reminds us that we can no longer fantasize about other worlds or realities. The tower has fallen; our connection to other realms and potential modalities has been severed. There is only this world, this universe, this reality. How is it shaping us? What will you allow to be obliterated, and what will you fight to keep alive? How do you live?