Oral History: On 'Sinners' and Speaking Plainly

There’s a satisfying comparison to be drawn between the act of eating someone out and the bloodthirsty desire of Sinners’ monster antagonists, an ever-growing coven of distinctly hungry vampires.

On a drive through cotton fields on a hot day in the Mississippi Delta, the charismatic and handsome Stack (Michael B. Jordan) is giving his younger small-town cousin, Sammie (Miles Caton), the key to pleasing a woman. To him, it’s all in the tongue. In sensorial detail, Stack describes a “button” at the top of a woman’s genitalia (or her “cooze”, as Stack puts it) that’s to be licked with the same intensity as one would eat an ice cream cone. This is the first of a handful of direct references in the film to orally pleasing a woman — it’s obvious that Sinners has cunnilingus on the brain.

There’s a satisfying comparison to be drawn between the act of eating someone out and the bloodthirsty desire of Sinners’ monster antagonists, an ever-growing coven of distinctly hungry vampires. Both the sexual act and the vampiric feed involve the consumption of a bodily fluid from a blood-rushed part. The mouth of the vampire and the lover are similarly placed on sections of the body that are vulnerable, delicate, and flushed with the blood-pump of adrenaline that comes from pleasure, from fear, or maybe sometimes from both.

While oral sex is shown only once in Sinners, the way that cunnilingus is discussed by humans and vampires reveals what I see as Sinners’ thesis regarding community. Where speaking plainly, even explicitly, is deemed principled and holds liberatory possibilities, avoidance and concealment, particularly under the guise of politeness, almost always aids evil.

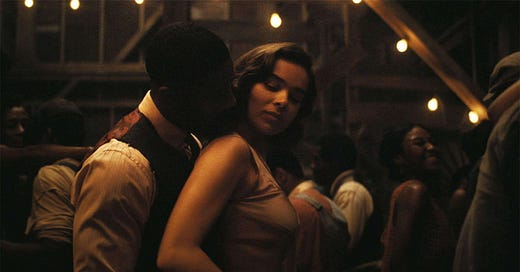

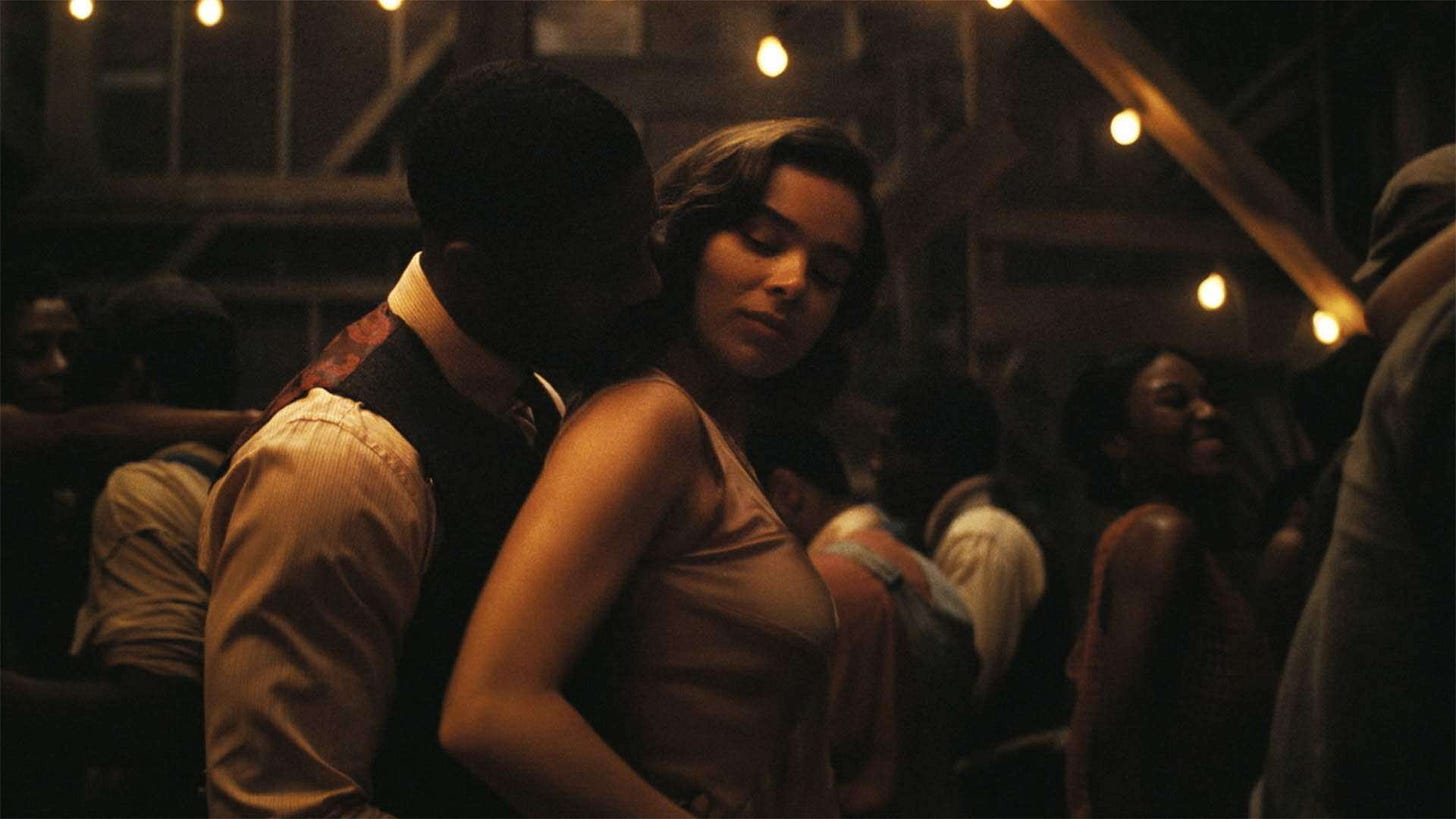

The Smokestack Twins’ insistence on direct communication — including during discussions of sex, death, and the threat of the Klan — elicits different responses. For the most part, those in community with Smoke and Stack reflect their communicative ideology. When Stack’s ex-girlfriend, Mary (Hailee Steinfeld), arrives in town to confront Stack about his ditching her in Chicago, we learn that Stack is not all talk in his advice to Sammie. Mary accuses Stack of leaving her after he “stuck [his] tongue up [her] cooze and fucked [her] so hard” (our second major cunnilingus reference, for those counting). Mary is immediately sketched as a plain (and graphic) speaker. In fact, she’s even more honest than Stack is able to be at first. While he skipped town without letting her know, choosing what he thought best for the two of them without informing her, Mary is willing to track him down to announce her anger at and affection toward him. Stack eventually confesses a reciprocal affection. In comparison to his brother’s more gradual willingness to open up, Smoke’s plain speaking comes easily. When he returns to his ex-wife, Annie’s (Wunmi Mosaku) home, he openly expresses the pain of their child’s death, his subsequent need to leave, and of the fact that he still loves and longs for Annie. Annie unselfconsciously shares her own complex feelings in return.

The Twins’ cousin Sammie is a unique case of plain speaking. While he’s somewhat shy when talking (a trait likely bred from his childhood as a pastor’s son), he is a mystically skilled musician. Sammie is part of a lineage of channelers who are able to use their musical capabilities to open up communication along their ancestral line. As fellow musician Delta Slim (Delroy Lindo) explains, “With music, we escape. Backwards to ancestors, forward to call that is yet to come.” When Sammie sings at the juke, the room is supernaturally and joyously filled with musicians that came before and after him; an ancestor in tribal clothing plays a drum, a woman in modern-day clothing twerks by a man DJ-ing. Sammie is also, ultimately, a disciple and benefactor of the Twins’ willingness to say it like it is. When he has the opportunity, he takes Stack’s advice and eats out a woman at the juke joint, telling her plain and simple that he wants to taste her.

But the direct communication that the Smokestack Twins’ community relies upon is anathema to the vampires of Sinners. Vampires tendency toward the polite and the indirect is often simultaneously a canonical mythical limitation and a useful tool. The vampires of Sinners are supernaturally barred from crossing any doorway threshold without an official invitation, a classic vampiric obstacle. But Remmick (Jack O’Connell) and his coven also rely on smooth-talking and subterfuge to infiltrate and hunt in human spaces, a skill that allows for them to appear as wolves in polite and respectable sheep’s clothing.

When an all-white vampiric trio show up at the Smokestack Twin’s juke joint door, the twins ask if they are Klan members. The vampiric group acts offended, despite the fact two of them are, indeed, Klan, and all three of them have plans to massacre the crowd inside. “Sir, we believe in equality and music. We just came here to play, spend some money, have a good time,” coven-leader Remmick assures. Remmick’s insistence that he just wants to have a good time isn’t technically a lie. He’s just following any good lawyer’s advice: the truth and nothing but the truth, but not the whole one.

Despite the polite and technical social performance utilized by vampires to conceal their monstrous othered-ness, these monsters also often read as sexually deviant. Examples of this abound: Salma Hayek forcing her hot vampire foot into Quentin Tarantino’s mouth in From Dusk Till Dawn, Twilight’s Edward Cullen inadvertently bruising his human girlfriend during sex with his raw vampiric strength, or the duo of Interview With The Vampire chewing on each other with lusty abandon and varying levels of explicit queerness, depending on the adaptation.

Sinners does not include any overt queerness, but as Harry Benshoff explicates in his analysis of queerness and horror, “The Monster and the Homosexual”, queerness can describe any act “focusing on non-procreative sexual behaviors”. Oral sex sits comfortably under that definition. And our attitudes around speaking about sex in general, but especially female oral sex, feels like a potent example of the great divide between the concealed and the plainly spoken. As Linda Williams writes in Screening Sex, “Cunnilingus puts the mouth and face in conjunction with a sexual organ that is harder to see; it is embedded in the labial folds that do not lend themselves easy visibility.” There are two options, then, to approaching the less visible sex act; one can consider cunnilingus destined to be surreptitiously performed, perhaps even taboo, due to the way the act itself is hidden by the mouth meeting genitalia, or one can receive illuminating guidance — direct advice spoken without evasion — and likely more pleasurably perform because of it.

Those that give, receive, and speak directly about giving head in Sinners are also those who speak without concealment. Information—be it emotional, pragmatic, or bodily— is offered and demanded without pretensions of politeness, as safety and pleasure are deemed more important. Intimacy is sought, shared, and advised upon in the form of sex and music so that that community at large can continue to both stay alive and access pleasure.

Even the other, non-oral sex acts of Sinners emphasize the use of the mouth. When Smoke and Annie have sex upon their reunion, she licks along and in the shell of his ear. When Stack and the newly-bitten Mary have sex in the back of the juke joint, she drools with newfound hunger. Stack happily accepts her offer to swallow some of her spit.

After her husband is changed, local shopkeeper Grace (Li Jun Li) — another plain-speaker, seen early on in the film happily haggling with Smoke over the night’s supplies– is targeted by the vampire coven. At the doorway they cannot enter without invitation, Remmick speaks to Grace in toisanese, saying, “[I] even know how you like to be licked. I promise I won’t bite too hard.” The implication is obvious (especially because, by my count, this is the fourth evocation of cunnilingus in Sinners, if we include the actual act itself as the third), but there is an aura of circumvention to the comment, at least in contrast with how oral sex has been discussed and portrayed up until now. The gap between visually seeing oral sex, or hearing outright “sticking your tongue up my cooze”, and the more allusive “knows how you like to be licked” illuminates the gap between the extremely direct and the purposefully oblique.

So much of the “good guys” and the “bad guys” of Sinners are reflected in one another — in fact, many of our protagonists become vampires throughout. In the same way sex and music can change the subjective passage of time, immortality obliterates our human understanding of it. In their respective libidinous and literal hungers, we constantly hear verbs like “lick”, “bite”, and” taste” from both monstrous and human mouths. But the manner in which they speak and act upon their intentions and desires are in deep contrast.

The vampires of Sinners function by subterfuge to access their needs and create their community. Remmick’s constant usage of the term “fellowship” in reference to the vampiric group is a bastardized one. People are changed into vampires by force, and their thoughts, memories, and feelings are shared in a supernatural hivemind used only to further deceive and threaten.

But the humans of Sinners function by manner of insistent and mutually agreed upon transparency. The pleasure of sex and music is illustrated directly, the vulnerability of grief and loss is shared openly, and the protective demand of information in order to keep safe as a black community in America is sought without pretense. Those in Sinners who wish to live pleasurably, safely, and truly accept this direct way of communicating with ease and reciprocation.

Sinners culminates, unsurprisingly, in a bloodbath. All of those who functioned under the guise of concealment — monsters of both the human and vampiric variety — are slaughtered, either by the rising sun or at the hands of those who speak plainly.

In contrast, those who are plain speakers are not rewarded, necessarily, with safety or even life. But they are placed on a path that is a direct reward of their ability to say what they mean and ask for what they need. Sammie is wounded and disfigured, but is the sole human survivor of the night. Smoke kills Annie at her request after she is bitten, before her soul can be trapped in the middling ground of the immortal. After a vicious gunfight with a murderous Klan group, Smoke reunites with Annie and their baby in a vision of a gauzy, white, summer’s day that is certainly their iteration of heaven. After being changed, Mary and Stack escape before the sun rises wandering America for decades afterwards, living at the very least as a lovingly bonded pair. Perhaps the fact that this coupling takes a little bit longer to shake out their feelings, get to the bottom of things, leaves them in a karmic situation where they are offered endless time.

Speaking plainly, using your mouth to say what you mean and to act on desire, is not going to inherently save you in the bodily sense. In fact, it may even put you at risk. But Sinners allows all of its characters who speak plainly vast spiritual graces in their attempts to share all that will keep them alive and keep them in pleasure. If everything of importance is shared, perhaps there’s nothing to weigh your soul down.

Film Daze is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to uplifting the unheard and underrepresented voices of the film community. While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our cause and keep us operating. This post was made available due to paid subscriptions. If you like what you read, subscribe and or share, cheers!