When I was very young, I had this recurring bad dream. I’m tiny and alone in an abandoned, dust-blown town. It’s turned to rust and grit: dry, sepia-coloured sand cakes building facades, is piled high in corners where structures meet, and blown like snow down the street by a hollow wind. It’s been apparently abandoned for years upon years – maybe because of an explosion, maybe apocalypse. I’m walking down the mainstreet lined with storefronts whose windows have been blasted through, all that is left of the glass is creaky, cloudy shards like teeth stuck in the splintered panes. Despite the broken glass, the displays still harbour something for show: chain hooks meant for bovine or pork hang from the ceiling holding up human torsos, only the torsos. No legs, no heads, no arms; just chests with limbs apparently ripped off. There are at least two per shop window, and they sway in the whistling wind, chains clinking. I look at them with silent horror, tears streaming down my face, my mouth agape, as I walk down the street helplessly, looking for my mother, any warm face. But there is no warmth to be found.

I would have this nightmare again and again, each time waking from it in tears and a cold sweat. I don’t know what I could have watched or read at such a young age for my brain to create this horrific terrain. It stopped returning to me at around age 10, but reared its lifeless maw about a year ago. When I told my friend about it, she said it reminded her of Silent Hill, the 2006 film based on the hit videogame of the same name. I watched Silent Hill recently and, though I found it to be unsuccessful as a whole, its visual monsters struck me as sublime. It got me thinking about nightmares in films, the vocabulary and cadence they take in the hands of filmmakers, and what they have to say about our collective fears and unconsciousness. (Spoiler: we seem to fear getting lost in abyssal unreality, not waking up at all, a great deal.)

Though horror films have always been nightmare fodder, I was able to find a few films about nightmares themselves, about our relationship with the fearsome and sleep. These films will likely stay with you in your waking and sleeping hours, morphing your thoughts to haunting proportions.

Carnival of Souls (1962) dir. Herk Harvey

The story of this film is in a way an artist’s nightmare. Carnival of Souls was Harvey’s baby. Shot in three weeks on a budget of $33,000, the film was his only feature and was inspired by the low-budget, understated work of filmmakers Elmer Rhoden Jr. and Robert Altman. Harvey secured all the funding himself, turning personally to investors for backing, and shot on location in Salt Lake City, Utah. The story was inspired by a looming pavilion in the city called Saltair Pavilion. Upon release, though, the film was hardly received, hardly seen, and, discouraged and disheartened, heartbroken, Harvey never directed another feature again. What a shame, for Carnival of Souls is a phantasmagorical marvel.

After church organist Mary (Strasberg-trained Candace Hilligoss) mysteriously survives a brutal car accident, she moves to Salt Lake City for work, only to find herself viscerally drawn to an abandoned carnival’s pavilion, a draw addled by visions of a creepy, ghoulish man who, appearing in mirrors, windows, and lurking in shadows, beckons Mary to the empty site. Whether a scepter, a nightmare, or real, Mary can’t ascertain. The film follows Mary’s pull and resistance to the mysterious man and the pavilion, which amounts to her slow descent into madness. The film looks beautiful, and Hilligoss’s pitch-perfect performance (a woman besieged by horrors while still habitually confined to a performance of femininity and decorum), Harvey’s naturalistic pace, and the spooky organ score (composed by Kansas City organist Gene Moore), all turn the story of simple action into a maniacal dance at the boundary of reality and dream. It’s impossible to forget this film, to not be haunted by its soul. What it means is largely up to you – I see it as an ode to art, and the loneliness that attends a love for creation – for at its core, the film is about life itself, a refusal to die.

Jacob’s Ladder (1990) dir. Adrian Lyne

Tim Robbins plays Jacob Singer, an infantryman deployed in Vietnam but sent home after a brutal attack. In New York City, Jacob begins seeing hellish beings – snake-like tails protruding from people’s backs, hazy figures like TV static manning cars that run him off the road. At a party, a psychic tells Jacob that he’s dead, and he laughs it off, but moments later, he watches his girlfriend penetrated by a demonic tentacle in an orgiastic dance that feels like the throb of a demented fever. The lines between reality and dream world are endlessly confused for Jacob, who begins dreaming about his life, a perfect life, before Vietnam – he was an academic studying Dante, with beautiful children and a loving blonde wife. Infernal creatures slowly encroach upon Jacob’s life and drive him beyond the brinks of insanity, to something veritably underworldly. In one of the film’s most frightening sequences, Jacob in the midst of psychosis is strapped to a gurney and wheeled into the bowels of a psychiatric hospital; as he descends lower and lower, the patients around him become less and less human, turn to deformed bodies with faces like death who lurch and sway and bang against the chain of the cages in which they are kept, in pain or ecstasy it is hard to tell. Jacob’s Ladder feels like a veritable waking nightmare because it fully crawls into Jacob as he lives through hell; it has us so totally become Jacob we find ourselves fearing his visions when we close our eyes.

In Dreams (1999) dir. Neil Jordan

Annette Bening is Claire, an artist who lives with her daughter and pilot husband in a town built next to one that was drowned to create a reservoir. The town is on high alert after a young girl goes missing, suspecting a killer at loose. When Claire has visions of a girl being murdered, she goes to the police to offer any assistance, but they laugh her away. When Claire’s own daughter is kidnapped and murdered by the killer, she realizes her visions aren’t of the past but of the future, and that what she is seeing in her mind is something more entangled than mere psychic visions – she shares a spiritual bond with the killer that allows the two to experience each other’s memories and actions. As her visions intensify, Claire finds it tough to tell her reality apart from the killer’s, to tell her dreaming mind’s digestion of the visions apart from reality, and her mind unravels. This film is brutal for how Jordan mercilessly and deftly blends reality with dream, leaving us feeling as disoriented and upset as Claire is; often what we begin to believe is a dream turns out to be fact, and vice versa. As with Jacob’s Ladder, it’s tough to take an objective stance when watching In Dreams, it’s tough to not abandon our hold of reality. This sense of having lost a steady, knowing grip on matters is deliciously augmented by Bening’s jarring performance – Claire is strangely straightforward, abrupt in her mannerisms, too ready to believe in the illusion, the nightmare.

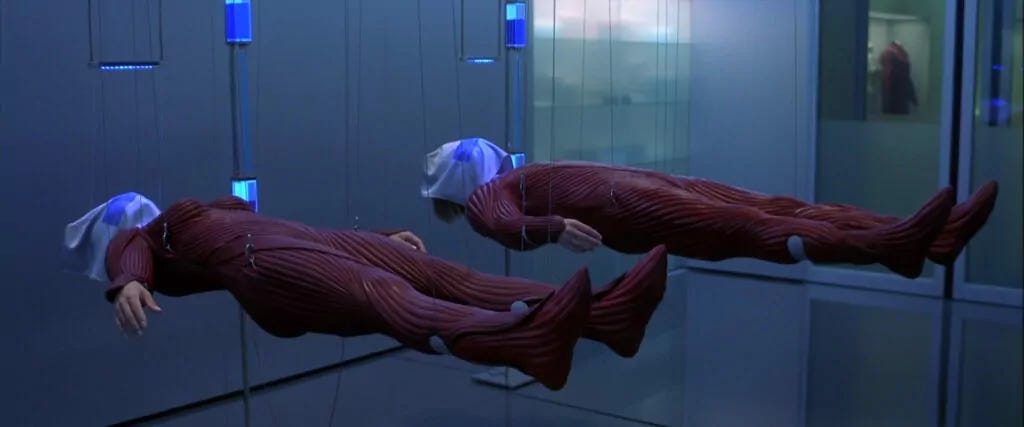

The Cell (2000) dir. Tarsem Singh

Singh’s The Cell shares plot points with In Dreams. A menacing and sadistic serial killer is on the loose across a few states, warranting the involvement of the FBI. The killer is apprehended very early on in the film, but falls into a coma at the moment of his arrest. One of his victims is still trapped somewhere and the FBI brings in child psychologist Catherine (Jennifer Lopez) to tap into the killer’s dreams and ascertain the location of his victim before it’s too late. The story is nothing to write home about, and Lopez’s performance is grating at best, her character a saccharine shade of the Madonna, of motherhood personified. What is marvellous about this film is its visual vocabulary and its dream (or nightmare) logic. As Catherine moves through the killer’s psyche, she learns about his past and his present in circuitous and terrifying turns, at the confusing and abrupt pace that dreams take. I truly haven’t been able to stop thinking about The Cell for its near Lynchian understanding of dream logic, for its images seem to have seared themselves onto my mind’s eye. This film, like all our most damning nightmares, is beautifully horrifying.