Editor’s Note: Our Cinema Club will either be a bi-weekly or monthly double feature selection curated by our staff. We took a break but are back to delivering regular new reads. Also, a friendly reminder that our paid subscriptions are currently discounted. A new paid subscription will be released early next week followed by our August Double feature. ICYMI Our Last Paywall Piece

Veronica’s Pick: Paper Moon (1973)

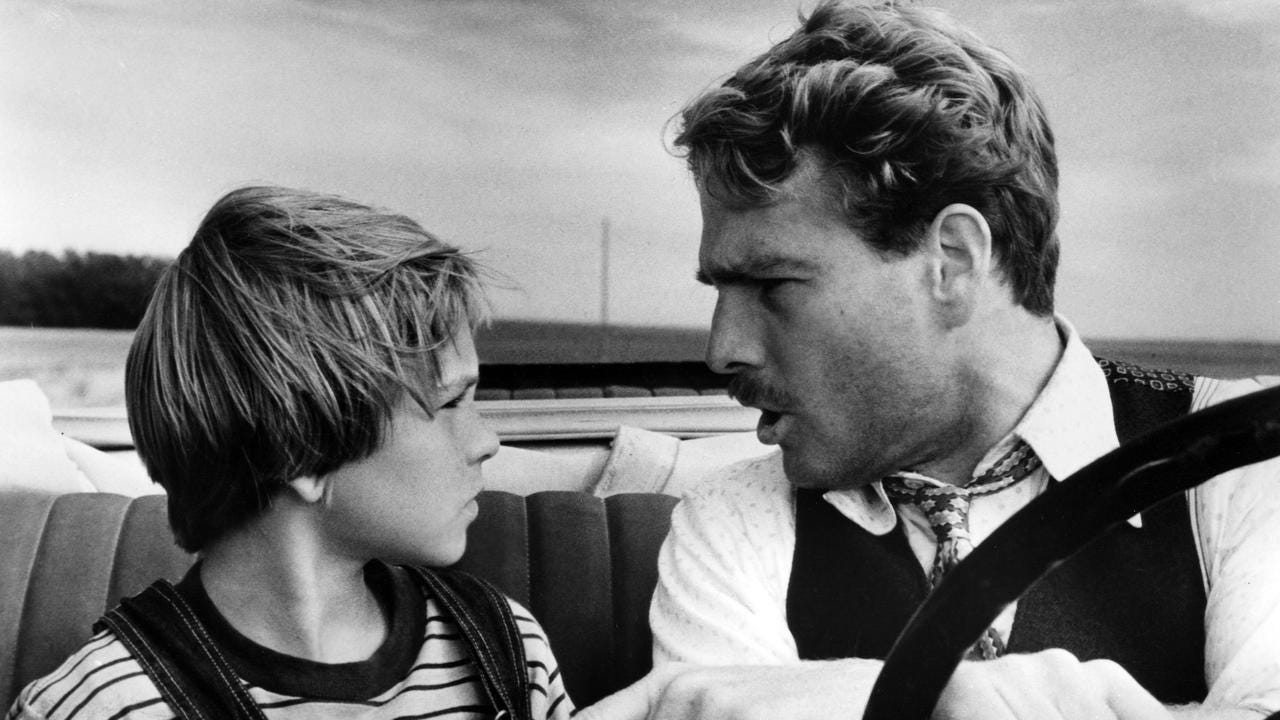

Released just a year before Alisha’s pick—the iconic Young Frankenstein—Paper Moon is a Great Depression 1930s pastiche, following con artist Moses Pray and his maybe-daughter Addie Loggins (played by real life father and daughter Ryan and Tatum O’Neal) as they road trip across farm country in hopes of finding some relatives to pawn Addie off to. Midway through the trip, Moses and Addie pick up performer Trixie Delight, played with high-toned, nasally ditz perfection by Madeline Kahn. Kahn is, as usual, a comedic scene stealer, and yet her true chops come from her capacity to imbue a scene simultaneously with the biggest laugh and an undercurrent of aching truth—evidenced by a particularly sweet, but frank, girl-to-girl back-and-forth with Addie out on a farmside hill. Kahn’s screentime in Paper Moon is relatively brief, but her performance is almost always what I think about first when I think about this film.

Alisha’s Pick: 1974’s Young Frankenstein

Mel Brooks and I have the same birthday — June 28. This year, he turned 98, and to celebrate, I turned with great delight to 1974’s Young Frankenstein. Unabashedly silly, and quintessentially Brooksian, the film follows the Transylvanian trials and tribulations of Gene Wilder’s Dr. Frederick Frankenstein, though he’d have you pronounce it “Fronk-en-steen.” Frederick is the grandson of the famously infamous Victor Frankenstein. Frederick hates to be associated with his late-grandfather, erupting with anger at the mention of the man known by many as a mad-scientist, and considered by Frederick simply mad. The young Frankenstein prefers to ally himself with cold-hard science, which stolidly dictates that dead matter cannot be brought back to life. Upon learning that he’s inherited his great-grandfather’s estate, out of which Victor worked, Frederick heads to Transylvania to scope it out. In the castle, Frederick finds himself viscerally drawn, perhaps even lured, to his grandfather’s life’s work, and after reading his journals, sees that the dead man’s experiments hold potential — It could work! Accordingly, he decides to continue Victor’s work of reanimating the dead.

A hilariously profound journey ensues as Frederick forges human life out of death in a masterful send up of classic horror. Brooks and Wilder are at their best as they mine not only classic film history, but also literary history, re-enlivening Mary Shelley’s timeless tale of craft, life, and death. What I love most about this tale, and about Shelley’s original, is the monster’s tenderness. It’s no secret that Shelley’s original story works as an allegory for birth, a fall from grace, and not just the burden of creation, but also the burden of being created. How do we exist knowing that we are capable of monstrosity? How do we create knowing we are accursed? The created being, thrust into existence, exists with a kind of folly that I’ve always found blameless, because perhaps it is, but also perhaps it isn’t — this certainly raises complex questions about free will, responsibility, and even culpability. Here, Peter Boyle’s creature, like Shelley’s, is a tender sweetheart, achingly desiring a rich life and embarking upon it with simultaneous fearfulness and gusto, relishing its pleasures, and weeping at its sorrows, some of which have been caused by his hand; still, he is alive fully and unabashedly, teaching Wilder’s Frederick about something more than the importance of life: the importance of feeling alive. This film is stunning and never fails to make me ache with laughter. Madeline Kahn is a marvel, and Marty Feldman is to die for. But most importantly, Gene Wilder is towering — loud, soft, careening, and jubilant, imbuing Frederick with a kind of strength and grace, not to mention hilarity, Victor would never have managed. This film is a celebration of what it means to be alive and to give birth to art, and Brooks and Wilder are worth celebrating for this creation.