ICYMI: ‘Princess Mononoke’: A Timeless Tale of Colonization and Indigenous Survival

November is Indigenous People’s Month and Studio Ghibli’s 1997 epic historical fantasy offers a poignant exploration of colonization, Indigenous survival, and man’s severed connection with Nature.

By Opal Nichols

It has been over 20 years since Studio Ghibli’s Princess Mononoke was released. To this day Hayao Miyzaki’s bloodiest work of animation, the 1997 epic historical fantasy offers a poignant exploration of colonization, Indigenous survival, and man’s severed connection with nature. November is Indigenous People’s Month in the United States, and then and always, the film, which contains an Indigenous main character and stark depictions of industrialization, becomes more relevant than ever.

The story is set in Japan’s late Muromachi period (approx. 1336 to 1573 CE), during a time of industrialization and expansion of the Yamato empire, what would later become the nation of Japan. The opening narration describes that in ancient times, man and nature lived in harmony with one another and forests covered the earth. However, as time went on and the earth’s great forests were destroyed by civilization, the forests that remained were left guarded by animal gods.

The first scene sees protagonist Ashitaka (Billy Crudup), the crown prince of his tribe, defending his village from being attacked by one of these forest protectors — the boar god Nago (John DiMaggio), whose flesh is ravaged by a demonic curse. Nago’s appearance in the valley is an unexpected disruption of nature; in fact, the villagers were able to sense the danger due to the odd behavior of other animals in the valley. Their connection to the land allowed them to notice disorder.

Prince Ashitaka is of the Emishi tribe, a real life ethnicity Indigenous to Japan. Not much is known of the origin of the Emishi people — one theory is that they may have been a collection of distinct Indigenous tribes inhabiting the main island of Japan. Ashitaka’s village would have been one of the last surviving groups of Emishi resisting the spread of the empire during that period. His native identity is integral to both the plot and his value system — Ashitaka believes that humans, gods, and nature should live in harmony.

After a short struggle, the boar god Nago succumbs to the curse before he’s able to destroy the Emishi village; but in the process, the curse is transferred to Ashitaka’s arm. The village wisewoman arrives to treat Ashitaka’s wound, pay respects to the fallen god, and perform burial rites. “Soon all of you will feel my hate,” said Nago to the humans as the curse overtook him, “and suffer as I have suffered.”

Later, the wisewoman explains to Ashitaka that an iron ball had been lodged in the side of the boar, which was responsible for the curse that turned him into a demon, the curse now afflicting the prince. The wisewoman tells him there is “evil at work” in the west, and that it is his fate to travel there and see with eyes unclouded by hate. The curse, she admits, will likely end his life if he is unable to find a way to lift it. Worst of all, due to tribal rules, Ashitaka would have to leave his homeland and never return. The generational impact of this moment can be felt as an elder cries out: “We are the last of the Emishi. It’s been 500 years since the Emperor destroyed our tribe and drove the remnants of our people to the east…. And now our crown prince must cut his hair and leave us, never to return? Sometimes I think the gods are laughing at us.”

s merely a consequence of man committing against nature the same sins that were committed against his people.

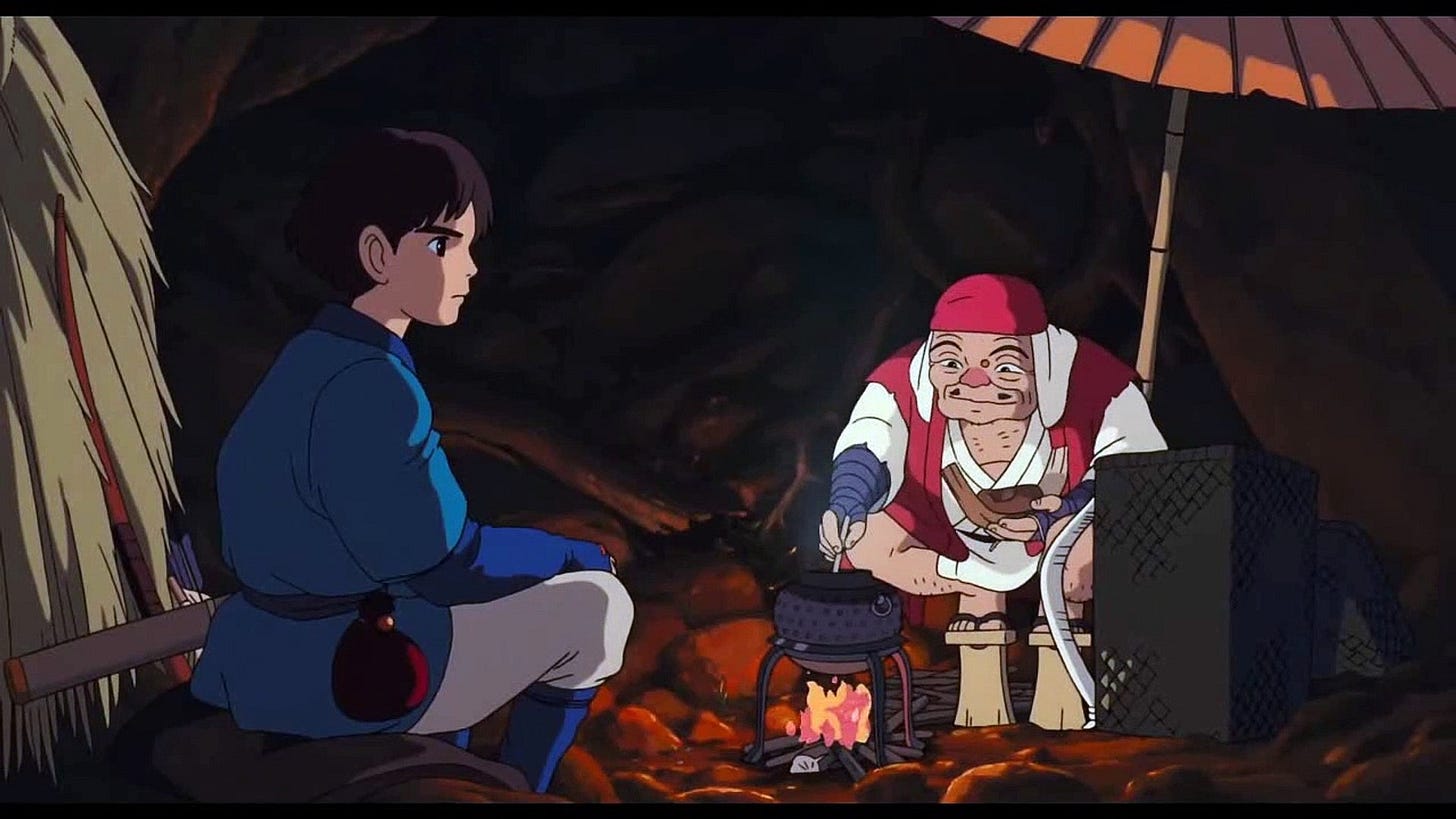

Ashitaka meets several people on his journey west, including the monk and mercenary Jiko-bo (Billy Bob Thornton), who suspects that the young prince may be from the Emishi tribe. Over a campfire, he promises not to share Ashitaka’s secret, and suggests that the young prince seek out the Great Forest Spirit in the lands to the west, a shapeshifting god that takes the form of a deer by day and a nightwalker after sunset. The two muse over the changing state of the world together. “These days, there are angry ghosts all around us, dead from wars, sickness, starvation, and nobody cares.” says Jiko-bo. “So you say you’re under a curse? So what? So’s the whole damn world.”

Ashitaka sneaks away in the early morning to continue his quest.

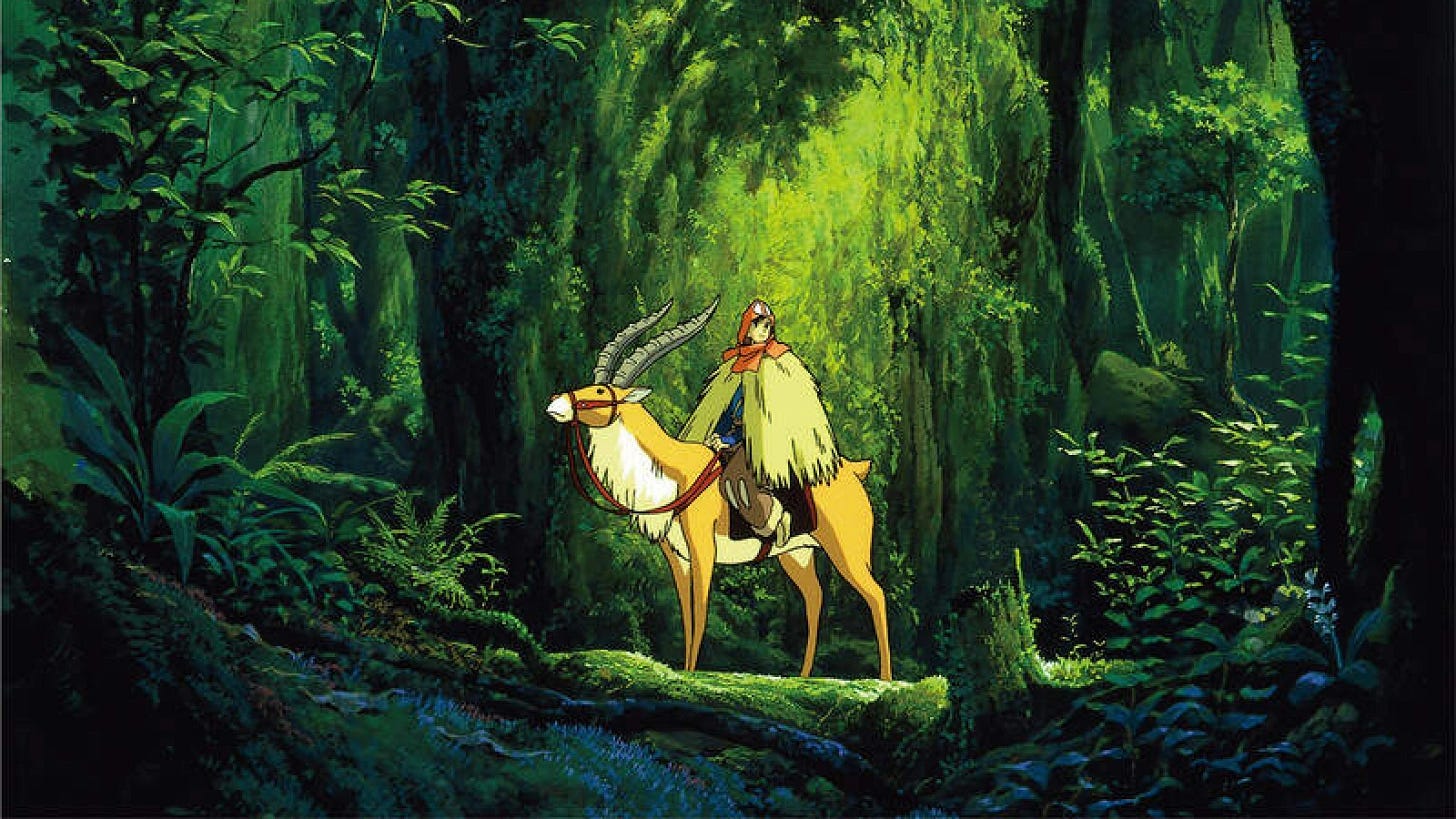

Not long after, the exiled prince has what is perhaps his most important encounter, with San (Tara Strong), the titular Princess Mononoke (literally: princess of the vengeful spirits). San, like Ashitaka, shares a different worldview from the rest of the humans — she was abandoned in the forest as a baby and raised by wolf gods. Her sole motivation is to defend the forest, her home, from outsiders attempting to destroy it out of greed. The outsiders, Ashitaka learns, are from the nearby human settlement Iron Town, run by a woman called Lady Eboshi (Minnie Driver). Their encounter is brief; he calls out to San asking if she is a spirit and she does not respond.

Upon entering Iron Town, Ashitaka receives a tour of the settlement and an invitation to speak with Lady Eboshi, the refined woman of industry running the town. Here he learns the origin behind the boar god Nago’s fate — that the forest he was charged to protect was cleared in order to build Iron Town, a town employing outcasts and lepers to process iron and forge weapons. Nago and his tribe of boars attempted to drive the humans out of his home, but he was killed with an iron bullet mined from his own mountain, subsequently turning him into a demon.

Lady Eboshi confesses that she did murder the boar god Nago for attempting to defend his forest. She apologizes to Ashitaka for his curse, but explains that the forest gods stand in the way of her being able to mine the mountain for its resources. For this reason, she is developing a weapon in hopes to kill the Great Forest Spirit. Despite this obvious brutality, Eboshi is a hero to her people — a confident leader who provides a safe haven for ex-sex workers and lepers, defending her people from neighboring threats.

The people of Iron Town seem to sneer at outsiders, especially the Emperor’s envoys who seek to capitalize off the town’s iron supply. The truth is that Iron Town is not much different than the colonial entity looking to acquire their resources — they, too, are willing to steal in order to extract profit and expand their way of life. They may be benefitting from the expansion, but they are benefitting due to violence. Eboshi may not think of herself as a colonizer, but she does not understand the forest, the land, or its inhabitants, and therefore does not understand the ripple effect her actions have on the natural environment. She believes the way forward is through eradicating the past.

The humans want to clear the forest, San wants to protect it; Ashitaka believes that harmony can be restored by bridging the gap between man and nature. It’s important to note that Ashitaka, unlike most of his fellow humans, still retains ancient Indigenous ways of knowing and caring for the earth. This knowledge was not mystically imbued, but forged through an innate relationship with the natural world. He is able to recognize spirits, sense danger, and rely on the land likely due to knowledge passed down through generations of his people. He has not only the desire but the education and skills to maintain balance between himself and his environment.

For Black and Indigenous people, seeing with eyes unclouded by hate is both a burden and our birthright. There is an innate knowledge that the way things are is not the way they’re supposed to be. The same is true for the humans in the film; in truth, there is a way to use the mountain’s resources without killing, but the colonizer’s greed requires speed and excess, a struggle for total domination. And a struggle ensues. When San attempts to kill Ashitaka for being on the “human’s side,” it’s as if they recognize something in each other — perhaps it’s that shared perspective and spiritual awareness. The two are able to forge a friendship over their mutual values. Many Black and Indigenous viewers will relate to the phenomenon of being in this world but not of it, having to navigate a society with values so disconnected from our ancestral ways of life.

After a fierce battle between humans and gods, Lady Eboshi and the humans are successful in eliminating the Great Forest Spirit and taking control of the land. This victory puts the future of civilization into question. The reality of Ashitaka and San’s shared fate is palpable — neither character is a part of this new world, but there is also no other world for them to return to. The two part ways as friends, with Ashitaka taking on the task of helping Iron Town rebuild after the battle, while San stays in the forest as she refuses to live with the other humans. In this way, San, being raised by spirits, may represent the past (Indigenous ancestors and their spiritual connection to the land), while Ashitaka reflects the future; specifically, the charge to forge a new world from the knowledge of our ancestors.

The film closes on the assumption that the industrialization of Japan continued as the age of spirits came to an end. The arrival of Iron Town on the western mountains caused decay and destruction to the natural environment, not unlike the pestilence brought about by European settlers on Turtle Island. Climate disasters continue to intensify with every misuse and abuse of the world’s resources, and Indigenous communities bear the brunt of these disasters while simultaneously protecting 80% of the world’s biodiversity (while only making up 5% of the population). Ashitaka’s dignity and bravery in the face of the erasure of his people, as well as his dedication to defending his home, are familiar to both diasporic black and Indigenous audiences. A feeling of walking a path that has been lit by your ancestors, or of longing for a life that no longer exists.

Now more than ever it’s important to amplify the voices and concerns of Native Americans across the continent; their communities are often the first to experience the fallout of the climate crisis. As the original inhabitants of this land, Indigenous people should be the foremost authority on how to properly care for the earth and restore balance to the environment. While we may not be able to reverse the effects of colonization and rapid industrialization, we can prevent further damage and safeguard our future by reestablishing our connection with nature. One of the many ways to do that is by centering Native American voices on how best to utilize and care for the land. There are organizations such as the Indigenous Environmental Network and NDN Collective dedicated to providing information on environmental justice, land reappropriation, and Indigenous sovereignty.

In the end, the death of the forest spirit lifts Ashitaka’s curse, allowing him to live freely and build a new life for himself apart from his homeland. It is clear that there is no turning back for anyone involved. However, this somber conclusion is given a more hopeful outlook by one thoughtful quote from earlier in the film: “Life is suffering. It is hard. The world is cursed, but still you find reasons to keep living.” The future is uncertain, but one thing is clear: it is ours to forge.