'Akeelah and the Bee': Respelling the Coming-of-Age Movie

Exploring the transformative and subversive nature of 'Akeelah and the Bee' and its intrinsic role to my upbringing as a Black woman.

You are now reading an exclusive piece from the Film Daze Digital Magazine, Issue 5: BLM. Enjoy! - The Film Daze Team

While I love a good musical or romantic comedy, coming-of-age stories are special because they are personal. They’re not typically rife with spectacle or reliant on a complex plot, instead reveling in the mundanity of life — the trials and tribulations that result from the social blunders and mishaps of one’s formative years. They implore audiences to find themselves and relate to the awkwardness of puppy love, the desire for popularity, and the wish for independence from our parents. Coming-of-age narratives are cathartic and relieve us of the embarrassment through an intrinsic sense of relatability. However, this fundamental relatability is complicated when you are a Black viewer.

The issue of representation in film has been particularly pertinent in recent history. Hollywood films, even with the strides that have been made over the years, still feature overwhelmingly white casts, with the coming-of-age genre being especially prone to it. When the coming-of-age film, hinged upon its alleged universality, fails to represent a diverse audience, the implicit assertion is that only the growth of white people is important. It places whiteness as not merely the standard, but as the only way. I had to grapple with this reality from a young age, as both a Black woman and a person who lives and breathes movies. I grew up, aged, and had experiences, all the while noting that the people I saw on screen, who similarly grew up, aged, and had experiences, looked nothing like me. I had to live with the dichotomy of knowing that I existed while being treated as if I did not.

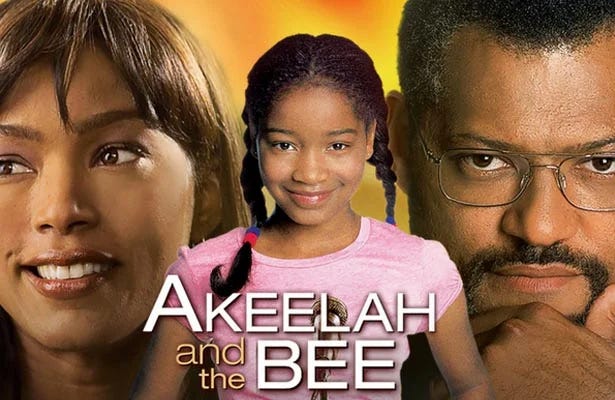

Imagine my excitement, therefore, when I stumbled upon Akeelah and the Bee. The film follows Black eleven-year-old Akeelah Anderson (a young Keke Palmer) as she prepares to compete in the National Spelling Bee. Akeelah and the Bee seems aware of the relationship between Black women and girls and film, lampshading this in an early scene: Akeelah sits on the city bus, traveling from her neighborhood in South Los Angeles to Woodland Hills to study for the Bee with a new friend. Akeelah is in a state of stress; she is not only riding the bus alone without her mother’s knowledge, but she is traveling to an area that she has never been to before. Akeelah momentarily looks out the window where a sight catches her eye: riding alongside the bus, drop-top, are three, young white women, who sing along to the rap song that blares from the speakers. Intentionally or not, this scene metaphorized the coming-of-age filmgoing experience for Black people. Akeelah observes a reality that has glimmers of her own but is not truly hers at all. The only thing physically separating Akeelah from the women is a glass panel and a few feet of asphalt but, despite sharing the same space, there is a striking disconnect — of race, of economic standing, of general being.

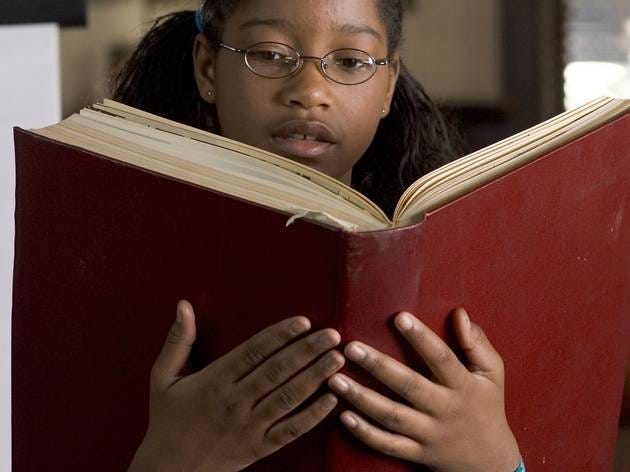

Watching Akeelah on screen served as the exact opposite for me. I was not simply watching, I was understanding and relating to the story in a way I had not imagined possible. I saw so many echoes of myself in Akeelah that it was almost overwhelming. Just like me, Akeelah was unambiguously Black, wore glasses, and was opinionated and honest. This was the first time I watched a coming-of-age film in which I felt seen and, as a result, my own coming-of-age felt validated. For once, the love I had for this medium was reciprocated.

Most galvanizing was Akeelah’s inviolable relationship with words — the backbone of the story. Akeelah is an exceptional speller, so much so (spoiler alert!) that she wins the Bee. Words emancipate Akeelah: they give her a voice in a world where she is often silenced and discredited by virtue of the intersection of her Blackness, womanhood, and economic class. A scene wherein Akeelah’s competitor, Dylan (Sean Michael Afable), is chastised by her father at the prospect of his losing the Bee to a “little black girl” makes her existential reality clear. While words may seem simple in the grand scheme of the universe, it is words that are the foundation to all that we know. In the same way Akeelah’s coach, Dr. Larabee (Laurence Fishburne), teaches her that all the big words in the Spelling Bee circuit are composed of smaller words, the crux of our existence is facilitated through words. Akeelah is vested with a power that Black women are so often divested from.

Akeelah and the Bee is not a perfect movie. The director, Doug Atchison, is white, which leaves room for a conversation about how ethical it is for a white director to tell a story that is centered around Black people in this capacity, and Dr. Larabee’s frequent rhetoric about Akeelah’s use of African American Vernacular English often veers into respectability politics. Nevertheless, it allowed me to feel seen and to imagine myself as powerful beyond measure — as brilliant, gorgeous, talented, and fabulous. Watching Akeelah’s light shine, a light that I saw inside of myself, gave me permission to similarly shine.

One of the film’s most well-known quotes is from Marianne Williamson:

"Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure. We ask ourselves, Who am I to be brilliant, gorgeous, talented, fabulous? Actually, who are you not to be? We were born to make manifest the glory of God that is within us. And as we let our own light shine, we unconsciously give other people permission to do the same."